- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- Primary

- Could a rekenrek transform how you teach times tables?

Could a rekenrek transform how you teach times tables?

When primary maths specialist, Amy How, first came across a rekenrek, she couldn’t see the point of it. “I looked at it, and I said, ‘why would I invest money in just another counting tool? It doesn’t make sense to me; I’m too frugal, schools can’t afford it.’”

The rekenrek is a type of abacus originating from the Netherlands. How was first introduced to it while working as a teacher in Canada, and although she remembers initially being sceptical, it didn’t take long for her to see its potential.

“The rekenrek tends to be thought of as an abacus, just for accounting,” she says. “When you translate ‘rekenrek’, the Dutch word, it means ‘accounting rack’. But I knew there was more to it than that.”

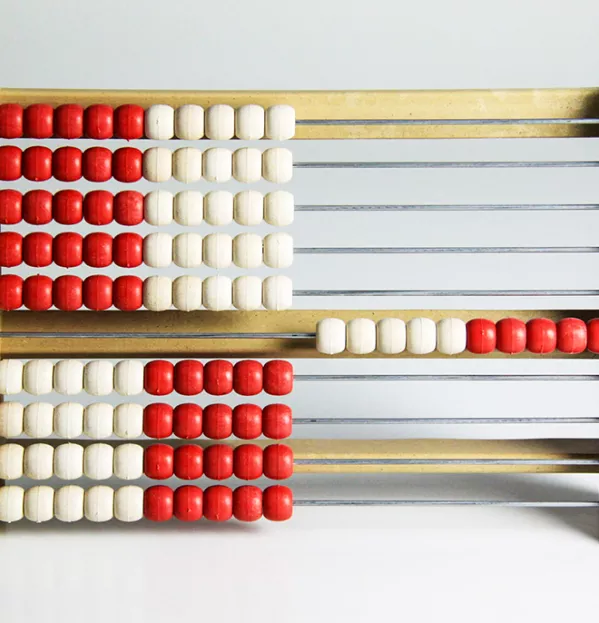

Like a standard abacus, the rekenrek is a counting frame composed of rows of wooden beads. Half the beads are red and half are white. The key difference is that while an abacus is based on place value - each row of beads is designated a quantity, such as ones, tens, hundreds or thousands - in a rekenrek, each bead has an equal value.

“So we don’t say, the red ones are worth this and the white ones are worth that,” How explains. “They’re all one; each bead is one.”

Lightbulb moment

Rekenreks come in different sizes. Twenty-bead versions, with two rows, are commonly used in the UK to help children develop number sense.

However, the rack that How uses is made up of 100 beads, split across ten rows. She hit upon the idea to try using this larger rekenrek to help pupils learn times tables. When she trialled the tool with a couple of pupils she was amazed by the results.

“All of a sudden, they were seeing things that I didn’t realise the rekenrek did, such as partitioning numbers and being able to look at a quantity and know how many there were, without having to count on their fingers,” she explains. “I started hearing what children were saying and watching what they did, and the light bulbs were going off. I thought, well, if this is going to work for the five times tables, will it work for the three?”

- Why Years 3 and 4 are the most important time for maths

- What’s the best way to teach times tables?

- Is this the ‘right’ way to teach early maths?

That light bulb moment led to How developing her own pedagogy for using the rekenrek with primary pupils. She has refined her methods over years of trial and error, working with pupils in Canada (where she taught for 17 years), in the Netherlands and, eventually, in the UK.

She has recently been awarded a grant from the SHINE trust, an education charity, to run a pilot programme in five schools in the North of England to improve the teaching of times tables in Years 3 and 4. The trial is still ongoing, but How says that initial results are promising, with pupils demonstrating increased levels of confidence and better fluency in recalling times tables facts.

Spotting patterns

So, how does her approach work? It all starts, How says, with pattern building. Initially, a whole day is spent looking at the patterning of whatever times table the class is currently learning.

Children “build” the times table physically, but unlike some other methods using manipulatives, this is based on repeated addition, rather than on arrays (arranging objects, numbers or pictures in columns or rows), thanks to the colour patterns of the rekenrek.

“The way it is colour coded, five red and five white, means you can start to partition number,” says How. “So if they’re doing their six times tables, they begin by pushing six beads over: that’s five red and one white.

“But the next time they’re pushing four white and two red, so they’re seeing that six is made up of five and one; four and two. Next one, it’s three red, three white. So all of those number bonds start to start to appear physically and visually in front of them.”

Because of the way the rekenrek is configured, pupils can “instantly see” an answer just by looking at it, How continues.

“So, if the answer is 36, they see three rows and six beads. They’re not counting, oh, I wonder how many in six groups of sixes - you can just see it,” she says.

Following the first dedicated day of learning, the class then spends a week taking part in practice sessions that involve the same process of exploring the times table physically through patterns and repeated addition and also writing the numbers out. As they go through this process, pupils will begin to spot patterns in the numbers themselves, just like in the beads.

“They start to see digits in one place start to repeat,” says How. “There are patterns in all the times tables, which are sometimes forgotten about.”

Daily practice

The next step is for children to undertake ongoing practice in the form of ten-minute daily sessions that take place separately to their regular maths lessons. This means they can be easily fitted into the school day.

These short practice sessions are really key to the success of the method, How says, “because memorisation starts to happen through a combination of repetitive practice and the patterning”.

The daily practice using the rekenrek also serves as a leveller, she adds: even if a child has already memorised a particular times table, taking part in the practice is “non-negotiable”. This “takes that stigma away from using a manipulative for all those children that need it”.

“It’s no longer a case that you’re using a rekenrek because you don’t know your times tables. It becomes a class-wide activity every single day,” says How. “And because it takes under 10 minutes, it doesn’t seem to bother anybody. You don’t sit there and go ‘well, I don’t really want to do this’, because before you know it, it’s finished.”

As manipulatives go, there is also another significant bonus: the rekenrek beads are fixed in place, something not to be underestimated in a busy primary classroom.

“There are no missing pieces,” How points out. “There are no double-sided counters being flung across the room. It’s zero chaos, mess-free, one per child, and off they go… it’s almost shockingly simple.”

How’s ultimate aim is to make more teachers aware of the possibilities of rekenreks, and to improve the teaching of times tables in as many schools as she can.

She is already well on her way: if her pilot programme proves to be a success, she plans to roll out her approach far more widely.

“It’s such a versatile tool that people aren’t using,” How concludes, and that’s something she hopes to change.

Amy How was one of the winners of last year’s Let Teachers SHINE competition. The competition, which is run by education charity SHINE in association with Tes, awards grants to teachers with innovative ideas to tackle the disadvantage gap. Entries for Let Teachers SHINE 2022 are open until 18 January.

You can find out more about How’s approaches through her website, ‘Rekenrek101’

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article