Book review: Wild Thing

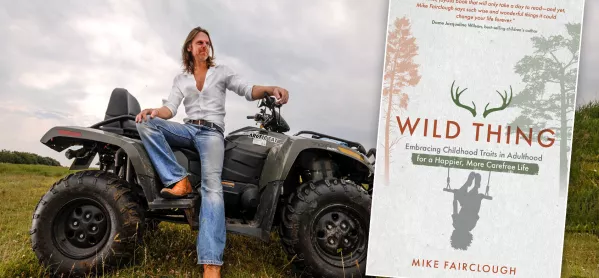

Wild Thing: embracing childhood traits in adulthood for a happier, more carefree life

By Mike Fairclough

Publisher: Hay House

Details: 160pp; £10.99

ISBN: 978-1788176286

I have to admit that Mike Fairclough’s Wild Thing is the sort of book that I would normally avoid.

It’s part memoir, part manifesto, part self-help book. It recycles quite a bit of psychobabble and, for me, a few too many sentences start with phrases such as “Research shows...” There are no footnotes or bibliography, and the reader is left wondering whether research does show any such thing and, even if it does, whether some other research may show something else altogether.

Some chapters contain lengthy (if no doubt accurate) summaries of theories on subjects ranging from creativity to cognition and gratitude to grit. The adulation of the Duchess of York and a number of other celebs doesn’t do much for me either.

But Fairclough has earned his spurs as an unconventional but deeply passionate and highly effective headteacher. His school in West Sussex has water buffalo grazing on neighbouring marshland, for goodness’ sake, and he takes visitors round to see them on the school quadbike. He is more than entitled to write and promote his book as he sees fit.

Playfulness and adventure

And what Fairclough says about wildness (or the lack of it) in schools will ring true for anyone who has tried to calm a class of children on a windy day - or, conversely, who has died inside as a school leader has started a meeting with the words “When Ofsted come in, they’ll want to see,” followed by a soul-destroying list of dreariness.

The book hangs on a series of striking and deeply personal anecdotes from Fairclough’s own life: from his Buckinghamshire childhood to the time he was grieving the death of his first wife and, finally, as he finds happiness with his second wife and their blended family of two boys and twin girls.

We climb a tree in a thunderstorm, plunge into a chilly river by starlight and experience the sensory overload of a visit to India. Even the daily bike ride to school provides an opportunity for reflection on the nature of perception and our perception of nature.

In this, Fairclough is a kind of modern Rousseau. For him, children embody the spirit of adventure and playfulness upon which the thriving of the human spirit depends. Adults, he says, are encouraged to deny these inherent strengths as they grow up, and we thus lose access to the life of the imagination and the creativity which flows from it.

The loss is ours as individuals, to adult society generally and to schools. We are trapped in what Fairclough, quoting the psychologists Yerkes and Dodson, identifies as the “comfort zone”, never experiencing the state of “optimal anxiety” that enables “rapid leaps in our personal development”.

As a teacher, are you an adult or a child?

One of the most inspiring teachers I have ever known played a game in which she categorised new colleagues as either “adults” or “children”. The “adults” would probably prosper in the profession and some would rise to positions of power and influence in their schools and beyond.

But it would be the “children” who would be loved in the school. They would be the ones who would bring life to their subject, magic to their pupils’ learning and really change lives for the better. And they would never start a meeting with a list of mindless inspection requirements.

And so it is for Fairclough. As he puts it: “As children, we naturally embraced the mystery of life, but due to the messages we may have received years ago from others who feared it, we grew to fear it, too.”

We desperately need teachers who embrace the mystery of life with children - who, like children themselves, are impatient to know more, to understand more and to live life more fully. We desperately need an education system where those teachers can thrive, be encouraged and be rewarded.

We desperately need more of them to become headteachers who, like Fairclough, are brave enough to channel Picasso and “learn the rules like a professional, so that you can break them like an artist”, for the benefit of our children and young people.

Rewilding is taking off in many rural parts of the country as a way of reviving the fertility of the land and restoring the health of communities. Mike Fairclough has provided a powerful plea for the rewilding of our schools and the souls of those who work in them.

Melvyn Roffe is principal at George Watson’s College, Edinburgh. He tweets as @roffeme

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters