- Home

- Giving up teaching to take on a headship is senseless

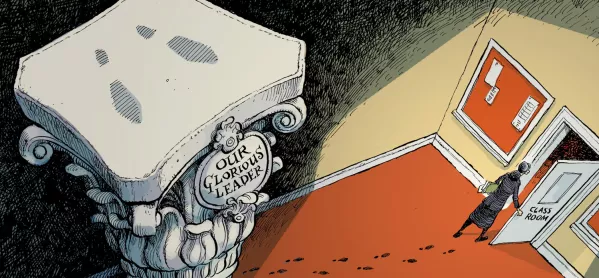

Giving up teaching to take on a headship is senseless

Those who can, teach. That’s been the on-message soundbite of education recruitment in recent years - dispelling the myth that teaching is for those who have failed at everything else in life.

Instead, rightly, it recognises that to teach effectively is actually one of the most demanding, challenging, stretching careers that you could choose.

It’s a great message - and not just from a recruitment point of view, either. In a world in which teachers don’t always command a great deal of respect, resetting these expectations can only be a good thing.

The problem, though, is that there’s a black hole of hypocrisy at the centre of all this - and I’m going to go out on a limb here and suggest that this unexamined hollow space in the teaching profession is causing some major problems.

Because for all of these pretty words about how important and highly skilled the teaching is, the fact remains that the higher you climb in your school’s hierarchy, the less likely you are to ever actually find yourself at the chalk face.

Let’s just examine that for a moment. Are highly skilled doctors promoted out of practising medicine? Is the prime minister excused from the requirement to be an MP? Of course not.

But in schools, the end point of many glittering (and not-so-glittering) teaching careers is a move away from the actual teaching.

This matters. It matters hugely because many of the unique challenges of teaching are only truly comprehensible when you’re experiencing them on a day-to-day basis.

The idea that, as long as you’ve done a few years in the classroom you are forever qualified to make decisions about what will and won’t work within it, is ludicrous when you start to consider it properly.

It is not that big a jump from the way in which everyone who has ever attended school as a student tends to think they know precisely how to ‘fix’ education.

Of course, the argument goes, you don’t need to be teaching yourself to spot the strengths and weaknesses of a school, to analyse the data or to write an action plan. And it’s true, you don’t. In fact, it’s the easiest thing in the world to spot a problem.

But if you’re going to maintain the fiction that you don’t want teachers working 11-hour days, you have to be able to make suggestions as to how these problems can be fixed. That is borderline impossible if you can’t remember what it’s like to have to fit two working days (one teaching and one administrative) into one.

Admin-plus

While I know that many school leaders are drowning under workload demands, juggling paperwork is not - I’m sorry - the same as juggling paperwork when you could be interrupted at any moment by children sent in from the playground for falling out.

It’s not the same as juggling paperwork and admin when you know the bell will ring at any moment and 30 children will suddenly need your cheerful focus - and you’re holding a still-full mug of tea in your hand that you once again haven’t managed to drink.

It’s not the same as trying to keep on top of your admin during your precious lunchbreak because you know that if you don’t, you’ll be up late trying to write insightful comments on children’s stories when you’re half delirious with exhaustion.

The thing is, even the very best managers can’t help but start to forget some of these teaching idiosyncrasies when they don’t actually have to teach, and there’s probably even some personal benefit for them in doing so: classroom amnesia means that if that Year 10 teacher isn’t meeting their target for GCSE results, then you can blame it on their poor performance.

If the class teacher in Year 3 keeps sending you the same child because of behaviour issues, then clearly his behaviour management isn’t up to scratch. (And if you make that clear enough to him, he’ll probably be too worried about his job to keep sending you children at all.)

If you can’t remember what it’s like to have your performance judged against factors beyond your control, then perhaps it gets easier to tell your staff to just get on with things: “We have to tick all of these boxes - Ofsted will expect it, so just make it happen. I don’t want to get into the nitty gritty detail of how: that’s no longer my problem, it’s yours.”

‘Not my problem’

Look, while everyone knows that there are terrible managers out there, I’m absolutely not saying that most are. But I do think it’s easier to dismiss your staff’s legitimate problems if they are problems you yourself no longer have to contend with.

On a more basic level, if you’ve been promoted to a team leader or deputy head because of your own excellent teaching skills, how sad that the upshot of this in many cases is that the children in your school will derive less benefit from them. That you will have fewer chances to inspire junior staff with your own expertise.

Obviously, senior staff do need time out from the classroom to engage in the other jobs involved in running a school. But it doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing situation and some schools recognise this. I know of schools where even the headteacher still takes classes - not because of necessity, but out of choice. And there are huge benefits to staff morale when this happens.

The derision that greeted the old Tory party slogan “we’re all in this together” came about because it patently wasn’t the case. Surely in schools, we can be better than that.

Esme Lyon is a pseudonym. She is a primary teacher in the south of England

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters