- Home

- Languages: We can do better for our bilingual students

Languages: We can do better for our bilingual students

“One language, one person; two languages, two persons” - Turkish proverb

The lack of a coherent languages policy is evident in England.

Our learning of languages is quite poor compared to many other countries (in 2016, we were voted the worst country in Europe for learning other languages).

Quick read: Why schools need to speak the same language on EAL support

Quick listen: Talkin proper? The standard English snobbery in schools

Want to know more? The problem with gendered languages

This is despite calls from industry (and others) to increase the number of pupils learning languages.

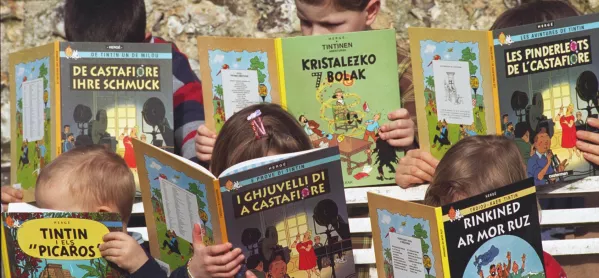

There is, however, a possible part-solution to this dire situation that needs to be drawn to the attention of policymakers: approximately 1.5 million young people in schools in England are either bilingual or multilingual in more than 300 different languages.

This extremely valuable and rich resource is largely untapped and little attention, if any, has been given to how their linguistics skills could be nurtured and developed to support the individual, the community and the country as a whole.

Learning benefits

The benefits of learning a language are well-researched and numerous. Research commissioned by the British Academy in 2017 found benefits in employability, trade, business and the economy, security, diplomacy and soft power, research, social understanding and social cohesion.

And numerous studies have found a positive impact on pupils’ attainment. Thomas and Collier’s research into the different approaches to the education of pupils learning English as an additional language (EAL) in the US proved that those who used their own language as well English attained higher than those who only learned English.

This is probably one of the reasons for the popularity and takeover of bilingual schools by middle-class Americans.

In England, research undertaken by Goldsmiths University has shown that those who attended Portuguese mother tongue classes “tended to significantly higher results than those not attending”.

This finding has been reinforced by research that found trilingual 11-year-old Gujerati Muslim pupils in Hackney told more elaborate stories and outperformed their monolingual peers in reading tests.

Over the past few years, EAL pupils have also overtaken their monolingual peers in attainment, although in reality the headlines mask the differential attainment of groups of pupils in this category.

And there are significant intellectual and cognitive benefits for those who speak more than one language. Research from York University in Canada found the constant exercising of the pre-frontal cortex by bilingual people led to attentional processes being reinforced. This resulted in better multi-tasking.

It also found that being bilingual considerably reduced age-related mental decline in certain executive processes, resulting in diseases such as dementia being warded off for longer.

A multilingual nation

It seems a long time ago, but the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games provided a perfect example of how we can be a multilingual and great cosmopolitan nation connected with people across the world. It may feel like a distant memory now, but for many of us it still gives hope of the type of positive society we can be living in.

One of the key drivers of speaking another language is to connect and communicate with others. Understanding the culture and having commonality with those who speak the same language is an integral part of who we are.

Schools may not directly prevent pupils from speaking other languages in schools, but they do not necessarily build on these skills or see them as a positive resource.

As a result, too many pupils in schools feel embarrassed and relegate the use of their additional languages to home.

But those pupils who do have the opportunity to develop their languages are more likely to see the bilingualism as a sign of flexibility and considerable sophistication with the ability to use translanguaging and code switching.

Young people who already can speak more than one language find it easier to learn another language than those that are monolingual.

A golden opportunity

Now is a golden opportunity for policymakers to become cognisant of the many benefits, and develop a coherent language policy that develops the teaching of languages for its monolingual pupils and builds on the languages spoken by its growing bilingual pupil population in the wider community.

This may even result in more monolingual pupils learning languages that are spoken among the growing diverse communities for genuine purposes out of the confines of the classroom.

Currently, as languages expert Jim Cummins states: “We are faced with the bizarre scenario of schools successfully transforming fluent speakers of foreign languages into monolingual English speakers and at the same time as they struggle, largely unsuccessfully, to transform English monolingual students into foreign language speakers.”

It’s time to recognise the incredible and remarkable resources that exist within our communities.

Sameena Choudry is the founder of Equitable Education, which tweets @EquitableEd

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters