- Home

- Long read: Should we scrap GCSE mocks?

Long read: Should we scrap GCSE mocks?

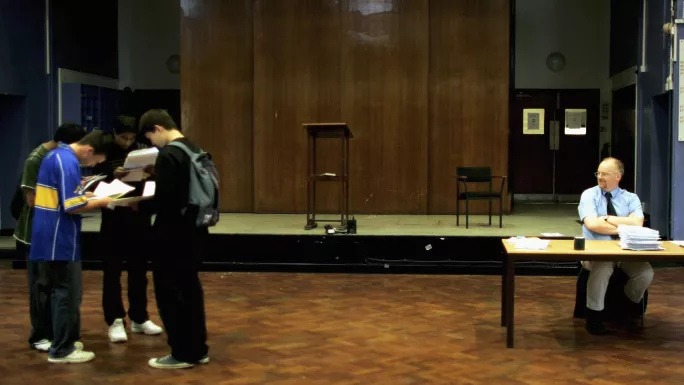

It’s a Wednesday morning in January. You should have a double lesson with Year 11, but instead you are sitting in the school hall, invigilating a GCSE mock exam for someone else’s subject. Considering the fact that you’re not even nearly through teaching your own GCSE course yet, this doesn’t seem the best use of your time.

But for as long as anyone can remember, GCSEs have been a fixed part of the school calendar. And as specifications get more challenging and accountability increases, some schools are placing even more stock in mocks - going so far as to hold multiple GCSE mock periods.

Question them at your peril - the benefits are obvious, right?

Well, maybe not. Maybe schools should cut down on GCSE mock exams. Maybe, according to some assessment experts, schools should even stop doing them altogether.

Challenging the wisdom of the GCSE mock

Why do we still do mocks? On the surface, the benefits are clear. They allow students to test their knowledge, and practise all those parts of an exam that revision can’t prepare you for: writing at speed, checking your answers and (speaking from experience) always remembering to turn the paper over to check that you haven’t missed out an entire essay question.

And many teachers believe those benefits are worth the upheaval they can cause in the teaching timetable.

“I think GCSE mock exams do have value,” says Rebecca Foster, head of English at St Edmund’s Girls’ School in Salisbury. “They allow students to experience the conditions in which they will be examined in the summer, not just in terms of timing, but also to experience being sat in the hall without the usual cues and comfort of a classroom setting.”

This is a view that maths teacher Katy Pembroke, who teaches at Cleeve School in Gloucestershire, shares. She agrees that mocks benefit “every type of student”, from the one who takes them seriously, does lots of preparation and reflects on the process, to the one who thinks they can get by without any preparation and needs the wake-up call of finding out that this might not be the case.

“In addition to this, teachers and departments get a clear picture of students’ strengths and weaknesses, both individually and collectively, and we can intervene to help accordingly,” Pembroke adds.

But the critics are beginning to circle. On blogs, on social media and in staffrooms, questions are being raised about the relative value of the process, particularly of those ramped-up, super-endurance GCSE mock periods that seem to be increasingly prevalent.

Mark Enser, head of geography at Heathfield Community College in East Sussex, is one of the critics. He believes schools need to consider the “opportunity cost” of mocks.

“GCSE mock exams seem to be getting more frequent in many schools and often result in several weeks of time lost from teaching,” he says. “This loss of curriculum time needs to be considered in a decision about whether the mock exams are worth doing.”

Another factor to consider, according to a maths teacher who wishes to remain anonymous, is the amount of content in the new GCSE specifications. Covering everything on the course is already a challenge, he explains, without also losing lesson time to multiple GCSE mock exam periods.

“My frustration is that I’ve lost three weeks of learning to pupils sitting mocks on whole GCSEs when we haven’t anywhere near finished the course yet,” he says.

Multiple crimes against workload

His school is one of the many now doing multiple GCSE mock exam sessions.

“I’ve lost twelve hours of teaching time with those classes and we’ll do another set in March,” he says.

Of the many teachers spoken to for this feature, the vast majority worked at schools planning multiple mock exam periods. While this might give students more exam practice, critics say it not only doubles the amount of time out of lessons, but more crucially for some, it doubles the marking burden, too.

“We are a small school with only around 100 pupils in Year 11, however [as there are three parts to the exam] that means that we have 300 papers to mark,” says the anonymous maths teacher.

“If we presume that it takes five minutes to mark a paper and five minutes to input the question level analysis into Excel, that is 50 hours of assessment and admin that could possibly be better spent elsewhere.”

This time cost of marking GCSE mock exam papers is a huge concern for many teachers and can be greater for some subjects than others.

Daisy Christodoulou, Tes columnist and director of education at No More Marking, analysed how long it takes to mark a set of English mocks. She found that, for one class, most teachers would need to spend a minimum of 10 hours marking.

“Given there are two English language papers and two English literature papers, one full mock takes 40 hours to mark,” she explains. “Imagine if you have to do two of those a year and you have two Year 11 classes!”

Of course, most teachers would happily spend this amount of time marking if they knew that mock exams were not just a means of gathering data for leadership, but were a genuine learning activity that benefited students.

Is this the case? Some researchers are not so sure.

Is it really learning?

“My problem [with mock exams] is that I am not convinced how to evaluate the success of the learning activity,” says Anders Ericsson, professor of psychology at Florida State University. He is best-known for his hugely influential deliberate practice theory.

He explains that, while many would say that sitting two tests and having the increase in performance between them measured is “the definition of the learning”, his preference would be to focus on “the ultimate goal” of the learning instead. To evaluate the worth of a class on anatomy or biochemistry, for example, he suggests looking at whether it is building the “necessary knowledge and skills to support professional work as a doctor”.

According to Ericsson, then, we should be questioning the value of mocks because it is difficult to show how far they contribute to a student’s overall learning in a subject.

Christian Bokhove, lecturer in mathematics education at the University of Southampton, agrees this is an issue.

“Recently there has been emphasis on the distinction between ‘performance’ and ‘learning’,” he says. “The key aspect here is that it’s not always the case that a good ‘performance’ - in the form of a good test score, for example - means that something has been learned.

“When we separate learning and performance in this way, mock exams do not always appear to be the best use of learning time compared to teaching ‘solid foundations’.”

On the other hand, Bokhove notes, there is also something called the ‘testing effect’, which refers to the theory that learning and memory are facilitated by the inclusion of practice tests in teaching or studying.

Research by Robert Bjork, distinguished professor of psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), for example, shows that the act of retrieving information from memory (as you might during a mock exam) alters how we remember it, making it easier to recall in future. And research by Henry Roediger and Jeffrey Karpicke found that the improvement in our long-term retention of information from testing is often greater than the benefits that come from additional study.

Bearing this in mind, Bokhove is inclined to believe that mock exams do have their place, as long as we recognise their limitations.

Likewise, Christodoulou suggests that the real issue here might not be the practice of holding mock exams itself, but how we go about holding them.

“They are definitely very time-consuming, so we should think very carefully about how they are scheduled, when they are scheduled, exactly what the purpose of them is, how reliable the data we get from them is, and how we will use that data,” she says. “Mocks are subject to diminishing returns - one might be valuable, but every extra one you do won’t add the same amount of value as the first.

“I do think you still need them, but I do worry that many schools are doing too many.”

Bokhove, similarly, thinks that schools need to change the way that they approach mocks if they want to make sure that the gains outweigh the costs. This is particularly true when it comes to marking.

“I have always been pretty surprised that, for formative purposes, we do not see more diversity of feedback being used in England. For example, peer feedback,” he says.

A compromise approach

Taking a more scaled-back approach, without ditching mocks completely, is a model that many teachers seem to favour. Both Foster and Enser support doing no more than one round of mock exams followed by “shorter exam-style questions” after that.

“Regularly attempting exam questions is important in terms of knowing how to improve and also building students’ confidence and ability, but this does not need to be in the form of full papers,” says Foster.

Meanwhile, Alice Stott, oracy lead at a secondary school in London, has another alternative; she suggests trying the ‘walking, talking’ mock, in which teachers lead students through an exam paper in real time by “talking them through each question at a fairly micro-level: explaining the strategy needed, modelling planning an answer, modelling their thinking process out loud and possibly writing their answer using a visualiser.”

Students sit together in the hall as a whole year group and complete the questions alongside their teachers. This gives them an experience of working to the timings they should be using in the real exam, while receiving coaching in how to approach each element of the paper, but without teachers spending hours marking.

“It’s an alternative to mocks in the sense that its not just putting them in the exam hall in silence for hours, with some students just sitting there staring at the wall with no clue as to what they are meant to be doing, feeling like they have failed and wasting time,” Stott explains.

But in all these discussions are we missing the view of arguably the most important people when it comes to mocks: the students themselves?

When commenting for this story, John Stanier, assistant headteacher of the Great Torrington School in Devon, was initially prepared to tell Tes “what a waste of time” mocks are. But that was before he spoke to his son, who is in Year 11 and has just completed his GCSE mock exams.

“He said he found them really, really useful and that the experience of sitting in the exam hall - feeling that pressure and actually being faced with an exam paper in cold blood was invaluable. It gave him a real measure of how much he knew and how much he didn’t know,” says Stanier.

“He didn’t need his exam papers marked to tell him this as it was clear to him what questions he could do and which ones he couldn’t.”

Pembroke had a similar experience, watching her own daughter go through mocks this winter.

“She was anxious to do well and worried that she might not have done enough [but] is now really clear on what the summer holds in store for her,” Pembroke explains.

So it seems there may be something approaching a consensus on mocks.

Are students being asked to sit too many mocks? Probably. Could the marking burden be reduced without harming a student’s chances of making progress? Almost certainly. But should we stop doing mocks altogether? It seems, for the moment, the answer is no: the mock exam shall live a while longer yet.

Helen Amass is deputy features editor at Tes

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters