- Home

- Support, sensitivity, solidarity: how to respond to the sudden death of a pupil

Support, sensitivity, solidarity: how to respond to the sudden death of a pupil

It was 6pm on a Thursday during the February half-term of 2018, and I found myself standing in my kitchen, staring blankly at my mobile phone, willing it to give me all the answers.

I suddenly felt completely alone. I could hear the babble of my four- and five-year-old children from the lounge getting louder, as my husband appeared in the doorway.

“Everything OK?” he asked. “Why are you making work calls? It’s half-term.”

I could tell he was cross.

I opened my mouth to speak, but didn’t know the words that would come out until the moment they did.

“One of my Year 11 pupils has been found dead,” I managed to say.

He looked at me, speechless.

“So no, I’m really not OK, not OK at all…but we’re going to put the children to bed and then I’m going to try to work out what I need to do…”

Quick read: Responding to the death of a pupil

Quick listen: How trauma can affect the behaviour of a child

Want to know more? Access bereavement resources from Mind

From the moment the two strange emails from the local authority arrived in my inbox asking me to make immediate contact, I had to make decisions on instinct. There was no guide handed to me, no school protocol to turn to, no one to walk me through it.

I look back at it now and wish I had known what I know now. If you find yourself having to manage such a tragic situation, hopefully you can benefit from my experience.

First response

As it was half-term, I knew I had to contact members of the senior leadership team to let them know before the story hit the press. The news had to come from me.

It may surprise you that I scripted these conversations. However, since reading Paul Dix’s book, When the adults change, everything changes, scripts have become a regular and vital part of most of the “difficult” conversations I have as a headteacher.

My husband reappeared as I was writing and offered advice. Ten years ago, he had spent seven months in Sangin, Afghanistan, on a really difficult tour on which they lost a large number of men. He’s always talked to me about the training they received with regards to “delivering bad news”.

He reminded me to ensure that there were little “niceties” at the start of the call, but to cut pretty much straight to the news I had called to deliver. He also reminded me that it was weird enough that I would be calling them during half-term: they would know it was not good news.

I planned six calls to key people. It turned into 10 when those I spoke to informed me of others who would be deeply affected and might benefit from hearing the news directly.

I couldn’t do any more than 10. I was exhausted. I listened to people’s silence; I listened to my colleagues weep in despair. And then I listened to them all, without fail, offer their total support going forward.

The local authority had informed me that I would need to represent the school the next morning at a rapid-response meeting convened within 24 hours of a young person’s death. Police, doctors, LA officials - this would be the group of professionals that would form the response.

I quickly realised I would need to decide who would come with me. And I wish I had known how crucial that decision would be. That I made the right call was purely luck.

I chose the pupil’s head of year - an experienced individual who knew the family well. She also knew the pupil’s older brother who had left our school a few years previously, and the younger brother who would be with us for some years to come.

She offered before I could ask. So did everyone else. I could easily have chosen someone from the senior leadership team, but in hindsight I realise this would not have been the best decision. The school had to fully function, and I would not be able to lead it in the same way as “normal”. I needed my deputies to be able to run the school during the initial stages of the tragedy, slightly distanced from it.

They had to enable the school to fully function. If we had all been reacting to the tragedy, and dealing with the huge amount of work and emotional cost that entailed, the school may have quickly frayed.

Day two

The next morning, we drove to the hospital. The police were there, social services, the school nursing team. We met for 90 minutes in a small meeting room.

It was surreal. We listened to information from the police that was detailed and difficult to hear. I wish someone had told me it’s at this point that you get the full story; that you are there to present the picture of the child that has died; that what you hear will deeply affect you; that it will stay with you for the rest of your life. I was not prepared for it.

We then had to start the “public” grieving process.

I wish I had known that where the first flowers were placed would become the focus of the memorials that followed.

We bought two bouquets and placed one on a bench just outside our main school reception. The spot was perfect; I wish someone had told me that what you needed in these situations was a place that’s safe, secure, monitored, accessible, but well out of general community (and potentially press) access.

That afternoon, we planned the following week’s schedule. We scripted the staff meeting that we’d called for 8am on Monday; the email calling the staff meeting; the Year 11 assembly that we were holding at 8.30am on Monday. We scripted the message that all tutors could read out to their tutor groups. We drafted the letter home to all parents and carers.

And then the police rang. The family had told them they were keen for us to go around that afternoon, as they knew we had both been involved in that morning’s meeting.

I knew it was going to be tough, but I wish someone had told me how unprepared you feel, how traumatic such an experience is.

It’s difficult to find the words to describe the deep sense of loss that filled their house and the devastation that they were (and still are) experiencing. The raw emotion was not anything I had yet encountered and it affected me significantly. We gave the second bunch of flowers to them.

Most of all, on that second day, I wish someone had told me it was OK to openly cry. That I needed to, even. I held it together. I promised to stay in close touch, gave them my mobile number and we walked back across the road to school. I shook. Then sobbed. Uncontrollably.

The first week

Over the weekend, we had monitored the social media chatter about what had happened leading up to the death of the pupil. I made direct calls to parents of the pupil’s best friends who needed support put in place at the school. My work mobile number went to a fair few parents, all of whom I am still in touch with informally today, even though their children have left school.

I sought clarity from the LA with regards to Year 11 pupils seeking physical reassurance from staff - in short, ensuring we were there for those in need of a hug. Staff, I knew, would be worried and I wanted to have a response for them.

But what I should have done earlier was talk to a headteacher colleague who had been through this already. I was eventually pointed in the right direction, but I wish this had happened sooner. As it was, that communication was invaluable for planning what happened next.

Monday morning was desperately sad. Supported by senior colleagues from the ed-psych service and the school nursing team, I read my (mostly) scripted briefing to all staff at 8am. I watched staff sob. Today, I can’t bring myself to read that briefing again.

The Year 11 assembly was worse. The pupil’s death was “unexplained”. We decided not to do assemblies for all other year groups, but deliver the set tutor message through an “extraordinary tutor time”.

Again, this was an off-the-cuff decision we arrived at - but it should be a concrete part of the process. Staff felt supported and could read the script without having to find their own words; the message was consistent; pupils all got the same message and we felt we were able to strike the balance between support for our grieving community and “business as normal” for the large majority of our learners who didn’t know the pupil.

I wish I had known that, as a school community, we would cry together more than you could ever imagine. And I wish I had known that this was very much OK. I stood at the front of the assembly hall and my eyes were drawn to our boys crying uncontrollably; our girls sobbing; staff not managing to hold it together. But we were all in this together and the culture of shared responsibility and support was palpable.

You have to allow the year group, and the friendship group affected by the pupil’s death, space and opportunity to grieve and recognise that this opportunity is simply not possible to measure or plan for, timescale-wise. Grief manifests itself in so many ways.

We gave our Year 11s the library. We enabled them to go there all that first week. We had professionals giving support and guidance to small groups and referring individuals for 1:1; we had pupils come and go; we had some stay the whole time. We monitored the visitors to ensure we were supporting them all.

Interestingly, the pupils taught themselves chess during this time and they still gather together to play it now.

Our year team played a huge role in supporting pupils. We have a reflection space in our year offices and this was significantly used during this time. Planned and ad hoc. It became a safe haven, a place to cry, be angry, to just talk and offload.

I wish someone had told me that the press would aggressively pursue me for a comment throughout this period, despite me making it clear on first communication that there was not going to be one from us until the parents were comfortable with us giving one. It was a shocking and unwelcome surprise that I was forced to call the editor and mediate for the family.

The first month

I attended the funeral representing the school alongside my head-of-year colleague. We also offered the opportunity, for those that wanted to, to pay their respects at the front of school while the cortege passed. I watched it back on CCTV when we got back from the wake and, having spoken to the staff who took part, it was so very moving.

I wish someone had told me to make sure all pupils who attended the funeral had their parents/carers with them. Not necessarily with them by their side, but waiting in the car park at least. Approximately 20 pupils attended, but only five or so had their parents with them. They were 16 years old and I get it, they’d probably told their parents there was no need for them to come, but this was wrong. Very wrong.

These 16-year-olds looked to us for all the support they needed to get them through what for most was their first-ever funeral. Providing the support was natural, but so very hard.

I wish someone would have told me that you really should go to the wake. We were politely trying to decline the invitation, worrying that we would intrude, but the family and his friends wanted us there. In truth, they needed us there.

School is such a massive part of young people’s lives that by being there, we gave the family reassurance that his friends would be supported. We told stories of his cheekiness and misdemeanours; we smiled and people thanked us. A lot. They thanked us for helping the school community through this tragedy and in anticipation of the support we would continue to provide.

We made our exit early and returned to school. Colleagues back at school needed to receive reassurance, too.

One of the best pieces of advice we received was from a Methodist minister and parent of one of the pupil’s friends at school. She kindly told us that with any memorial service that the school was planning, we should try to do it as close to the funeral as we could. Pupils and staff were very keen to have our own service in school. The minister helped us plan it and, although it had no religious angle, she gave great advice.

I wish someone would have told me to seek advice from the local church sooner. It was only because she was a parent and offered herself forward that we were able to benefit so much from great advice.

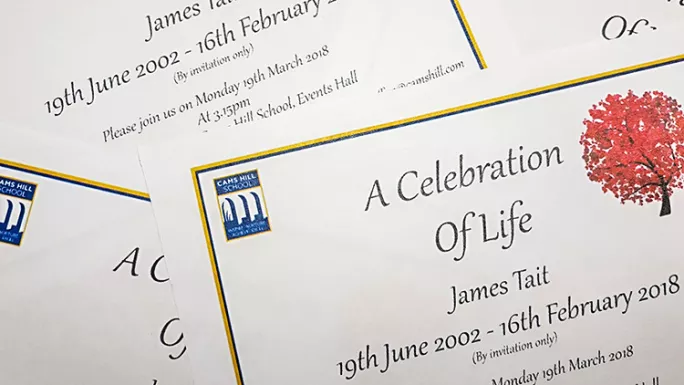

We carefully planned a celebration-of-life service and closed the school 15 minutes early, as a mark of respect, to start the service.

I wish someone would have told me that small gestures such as these would be so well received by the community.

We laughed. We cried. We lit candles. We gave his family a memory book that pupils had signed. And the most amazing part of the whole service was listening to his mum speak. We had asked her if she wanted to and she had said that she would try, but that she wasn’t sure whether she actually could.

She is a remarkable lady and came equipped with notes to speak to all of us, but most importantly, to his friends.

She spoke of her and her family’s thanks to them for being their son’s friend and to them for supporting each other through their grief.

She spoke of her and her family’s grief.

She spoke of how they were consoled by the overwhelming support of, and from, our school community.

And she told her son’s friends that they must, for her sake, focus on preparing for their exams. It was the most emotional moment when she told them that they needed to get their exams because her son couldn’t, so they needed to do it for him. It was the message that gave our pupils the permission to begin to move forward. It was incredible.

The first six months

And so our school community began to move forward. We asked the pupils and his friends if it was OK to clear the flowers from our memory bench. I am so glad we asked them - this should always happen.

We attended the inquest. A narrative verdict was recorded. No one would ever really know what happened.

His birthday was in the middle of the GCSE exams. The prom was hard and exam results day harder still. But we got through it together.

The first year

By the time this is published, it will be nearly a year since his death. It still feels like yesterday. I popped in to see his family recently and told them we still think about him every day. We do. And I do.

I’m about to start work on a guide to support other headteachers going through a sudden pupil tragedy in their school communities. It’s my way of trying to make sure no one ever has to go through what I went through in the same way ever again.

I wish someone would have told me so very many things. We need to help each other more in this fabulous profession. The sad reality is that it will happen and has already happened to others.

Gwennan Harrison-Jones is headteacher at Cams Hill School in Hampshire. She has written this article with the permission of the pupil’s parents, and in tribute to them and in memory of James, 19 June 2002 to 16 February 2018, who died aged 15

Further reading

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters