- Home

- Welcome to the most controversial school in Britain...

Welcome to the most controversial school in Britain...

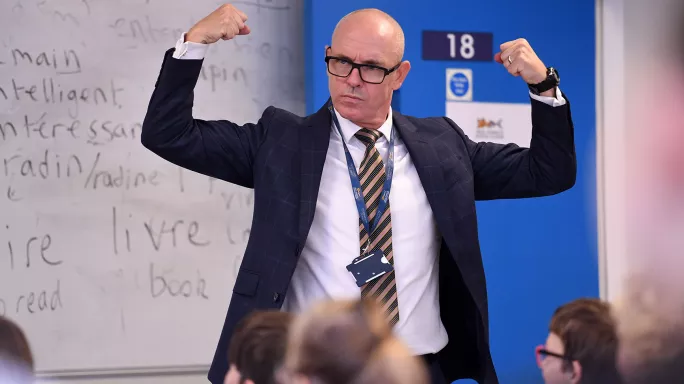

Barry Smith is proving a point. He leads me around the corridors of his school at a manic pace, bursting into classrooms seemingly at random. And once he has thrown himself in front of the pupils and their teacher, he begins to chant poetry - Invictus, Oziemandias or the like. Remarkably, the teenagers then all put their hands on their chests and bellow the words back in unison.

In every single classroom we bundle into, he does the same. In every single classroom, every single student chants the words back. In every single classroom, Smith commands unwavering attention. He sometimes even takes over the teaching - it doesn’t matter what subject - and the teachers don’t seem to mind.

If you know Great Yarmouth Charter Academy (GYCA) in Norfolk, or rather if you know the reputation of the school on social media since Smith took over, this may not surprise you: he was once deputy head of London’s notorious Michaela Community School, which is known for no-nonsense behaviour management and routines of chanting of the kind on show here.

But if you do not know the reputation of the school, if you take it simply as it appears, this sort of routine seems truly bizarre. This ought to be a largely unremarkable school in a largely unremarkable coastal town in East Anglia. Serving a deprived (53 per cent pupil premium) catchment, battling socioeconomic headwinds, this could easily be one of hundreds of secondaries quietly and efficiently going about their important work.

Yet, in the decade I’ve been doing this job, this is the most intriguing school I have ever visited. And the reason is almost entirely down to the bizarre genius of Barry Smith.

Full metal suit jacket

Until last summer, this was a school in a mess. Behaviour management had completely failed, and had been failing for almost as long as anyone in the town could remember; perhaps inevitably, the results were rock bottom. They were among the very worst, in fact, in Norfolk and Suffolk - an area already renowned for underperformance.

And then, in the summer of 2017, after a long battle, the school was handed to the Inspiration Trust, a multi-academy trust headed up by CEO Rachel De Souza and chairman Theo Agnew, before he was appointed schools minister earlier this year.

The pair, known for their formidable combination of educational astuteness and political savvy, then did something uncharacteristically risky: they appointed Smith as headteacher.

Smith had a sizeable social media reputation. He was a vocal “traditionalist” before that phrase had become common currency in educational debate and, after ploughing this lonely furrow for years, Twitter provided the forum to discover that he wasn’t alone. When he took the job as deputy head at the nation’s most vocal traditionalist school - Michaela Community School - his position at the top table of trad-teaching was secured.

Headlines follow Smith pretty much everywhere he goes. For example, at Michaela, his name hit the national newspapers in 2016 when he sent a letter to parents warning that children would be put in “lunch isolation” with a rationed lunch if school-meal fees went unpaid.

In short, his reputation is that of the sergeant major from Full Metal Jacket (“What is your major malfunction?!”) meets the PE teacher from Kes (although he’s a linguist originally). The broad Tyneside accent somehow adds to this impression.

He has not kept his head down in his first headship - quite the opposite. Since his arrival, GYCA has become a regular in the news pages. Most famously, he issued a diktat banning so-called “meet me at McDonald’s” haircuts. And then there was the memo warning that kids should not be allowed out of lessons if they felt unwell, but instead be handed a sick bucket.

This would have been radical in London, where such extremities are sometimes tolerated; in Great Yarmouth, where the school is one of very few secondaries, it was like playing a gangster-rap album at the local old people’s home.

If you are to believe the local coverage and social media, many parents revolted, withdrawing their children in droves, horrified by Smith’s behaviour-management regime. There was even a demo in the centre of town protesting against his approach.

The controversy reached such a crescendo that regulator Ofsted ordered a special inspection in February. In Great Yarmouth, if they thought this was to be the end of what they believed to be a bizarre, trippy nightmare, they would be disappointed: the inspection exonerated Smith and his team of any wrongdoing - and even praised its improvements.

Into this context, went I: expecting a boot-camp, children cowering in corners, a dictator at the helm.

But that was not what I found.

Respect: find out what it means to Barry

GYCA feels very much like a happy school. The corridors at transition are not silent; they are ordered - which is hardly surprising given the staff member situated on every corner - but there is a buzz, as the students talk to the teachers and teaching assistants, and vice versa.

Indeed, they are encouraged to greet one another politely at every opportunity and make small talk - banter, even. “Hello sir/miss, how are you?” abounds everywhere.

The impression you get is that this is a quietly organised school in which respect, not discipline, is the number one priority.

Given that the kids apparently ruled the corridors until very recently, this is no small achievement.

For example, two teachers told me a story about how, a few months earlier, the school had called out an electrician because the lights in the communal areas kept turning off. The sparky pointed out that they were controlled by a motion sensor. But it had previously never had a chance to kick in because, prior to Smith’s arrival, there had always been students running around in the corridors during lessons. The lights were always on; now they often turned themselves off.

How does one undertake such an apparent change in behaviour in such a short period of time?

The first thing to note is that Smith is avowedly not an advocate of “no excuses”, an expression often used as shorthand for an approach to behaviour that doesn’t allow for nuance or, well, excuses.

“I hate the ‘no excuses’ phrase. It’s lazy,” he states. “Someone will no doubt find in the annals of time an example where I’ve used it, but it’s unhelpful because we’re all human and this is all about relationships. We’re not all fluffy-fluffy, of course, but this is about adults being adults and being able to judge situations. I call it ‘warm and strict’.

“I used to love reading transcripts of Sir Michael Wilshaw’s speeches. I used to love it. And he would talk about giving them love - but tough love. For me that was YES. You want adults taking responsibility, making sure that children take on that responsibility.”

But what about all the stories? The haircuts, the sick buckets?

“I’m going to nag about shoes and haircuts,” he replies. “I’m going to nag about skirt lengths and I’m going to nag about great big eyebrows on girls. I like one haircut, one head.

“The vomit bucket was a flippant, funny comment. The kids know me. We are not child haters. If a kid isn’t well, we take them out of a lesson, take them to the office, give them a glass of water, he’s fine.

“Remember, we had a culture at this school where kids were permanently out of the classrooms.

“I want the staff to be a force of nature with the kids, to be positive; I want the whole place to buzz with positive energy. That means high standards, that means good eye contact, good chinwags…”

He suddenly bellows, “HELLO SIR, HOW ARE YOU TODAY”. And then he continues.

“I want it to be full of a little bit of banter; I want to bounce off the kids, get their dimples going, make it a happy place. We do this job because we like kids.

“I do want absolute silence when I’m teaching. But a kid happy at school is one who is made to work hard, but has a head that is buzzing with ‘wow, I’ve learnt lots’. That’s what a school should be.”

‘I don’t have the highest regard for most teachers’

But how true has this change in behaviour really been? Is this a school that has actually gone from what was reported to be chaos to a haven of learning based purely on some rules of respect and tough love?

Well, the results are promising. In the August after my visit (at the end of last term), the school’s GCSE results rocketed from 30 per cent achieving a grade 4 or better in English and maths, to 58 per cent - one of the most improved in England.

Norfolk, like most of the country, is suffering massive teacher shortages and this transformation has been achieved with largely the same group of classroom teachers that Smith inherited. This isn’t a new free school - he had to work with what he’d found (alongside a senior leadership team handpicked by Dame Rachel).

“This was about galvanising the troops,” he explains. “I’ve met a lot of teachers. I know what makes them tick.

“I don’t have the highest regard for most teachers. Too many teachers are praise junkies. They’re observed and get appraisals and they give people what they want. But teachers need to think for themselves; what if Ofsted said we want you to hit children with sticks?

“I want teachers to have pride in their subject, pride in their delivery, pride in the kids - it’s all combined.

“When I arrived here I thought I was going to inherit a bunch of dreadful people, but I haven’t, I’ve been very lucky. They’re great.”

But what of the students, was he lucky with them, too? Has he turned them all around and persuaded them to stay through sheer force of personality? Has he turned around results with the same children he inherited?

For all the tales of haircuts and sick buckets that can be neatly batted away, there is one story that sticks. This is the question of just how many kids were removed from the roll during Smith’s 12 months in charge.

Indeed, in the summer after my visit, a freedom of information request by a local parent revealed that 81 pupils had been “removed” from the school’s roll since Smith arrived. These included 38 pupils the local council said had been taken out of the school to be home educated; 32 transferred to another secondary; and five who had been permanently excluded.

Out of a roll of less than 700, these numbers are striking. (Although, as Smith is keen to point out, 71 students also joined during this period and, as of this September, the Year 7 roll was substantially up year on year. In a statement, the Inspiration Trust was keen to point out that the number of pupils home-educated across the whole of Norfolk had substantially increased, too.)

As I broach the subject, Smith, normally so effusive, suddenly becomes guarded.

I ask him how many kids he excluded in his first year.

“Less than last year [2016-17], I know that,” he says. “Definitely single figures. There was one that broke a teacher’s finger, three or four had consistent bad behaviour; this school was in chaos - I’m not going to go into too much detail. I am very honest and people use that against me.”

I decide to push that honesty a little. Does Smith feel responsibility for those kids who leave the school?

“Look, I take responsibility for the kids that are here,” he replies. “I said when I arrived, I’m going to reclaim this school, and we have reclaimed this school.”

And then he says something unusual.

“If you have 100 kids in a school, 10 kids will be fantastic: whatever happens, they will do well. Eighty kids could step into the dark side given the opportunity, but we’re going to reclaim that school for those 80 kids. Then there are the 10 naughty kids who will come on the journey if they want to, but you can only take a horse to water. ”

How many of those “naughty” kids at GYCA have come on board?

“Most kids have bought in,” he says. “People are like water: they assume the shape of the vessel they are in.”

But, it would seem, not all of them.

Not that any of this seems to worry those working in the school, at least not openly. The staff, from dinner ladies to assistant heads, almost literally queue up to tell me how amazing things have been since Smith arrived. I am paid to be cynical and it’s hard to maintain it in these circumstances.

Within this context, the chanted poetry makes sense, as does the almost Victorian approach to uniform, haircuts and sickness. This is schooling as a quasi-religious experience: the repetition, the passion, the belief.

Smith’s charisma and enthusiasm meant I, too, wanted to become a believer - and in many ways I did. Truly, Smith is transformative. He is in the process of saving the education of hundreds of kids and the professional lives of many scores of teachers. For them, things are probably going to be OK. Maybe even better than OK.

But this will likely come at a cost: a significant number of kids simply aren’t going to find space on Smith’s educational lifeboat.

Ofsted does not seem to think there is a problem. Smith does not seem to think there is a problem. And it appears the staff don’t think there is a problem.

One teacher stopped me as i was leaving to say the following: “The day after Smith arrived, I had to stop in my car on the way home for a cry. I knew that, finally, things were going to be OK.”

Quite whether the parents of the children who have left the school share that sentiment is open to speculation. And what about the education system? Well, the answer to that question would tell us something very interesting indeed about how the school sector views itself.

Postscript: The Great Yarmouth Charter Academy has also been involved in a local controversy surrounding its merger with a local free school, Trafalgar College, which is also run by the Inspiration Trust. At the time of my interview, Smith was unable to comment for legal reasons. Since the interview, an application for a judicial review of the merger has been rejected by the High Court

Register with Tes and you can read five free articles every month, plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £4.90 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £4.90 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters