My daughter recently said the words that every school leader dreads to hear: “Daddy, when I grow up, I want to be a teacher.”

Don’t get me wrong: I love my job. But teaching has a workload problem. The last thing I wanted was to watch my daughter drowning under the piles of planning and marking that I saw staff struggling with every day.

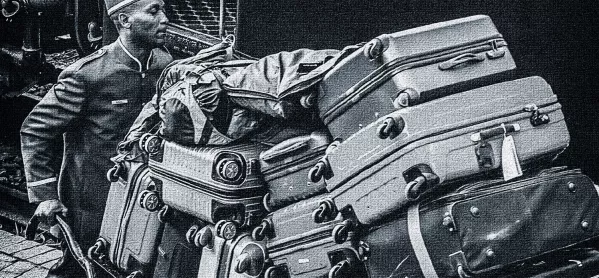

As an executive headteacher, dictating the marking policy for three primary schools in Enfield, North London, it should have occurred to me then that I might be part of the problem. However, the penny didn’t drop until a couple of days later when I ran into one of my NQTs wheeling a suitcase out of school on a Friday afternoon. I asked her if she was going anywhere nice for the weekend. Her response was: “No, Matthew. This is your marking policy.”

I realised that the reason I didn’t want my daughter to be a teacher was down to something I could fix. What if, instead of expecting teachers to take books home, we got children to do all the marking in school? This is exactly the policy that we have been implementing at my three schools. After a term’s trial in September 2016, we took the plunge and have not looked back.

So, how did we get to this point?

It may be slightly unoriginal, but I like to blame Ofsted. In 2014, the inspectorate said that lessons would no longer be graded and that it would instead look at progress over time. We interpreted this as being “all about the books” and so set up the most comprehensive marking policy known to education. Once a week, teachers had to mark a piece of writing in depth, providing a positive comment, target and task for improvement. After pupils completed the task, the piece was marked a second time and the child had to reflect on this second mark. It was madness.

However, Ofsted did not prescribe this crazy marking. It was me. I was creating a toxic workplace where I was struggling to recruit or retain good people - a workplace that I did not want my daughter to enter.

Teachers were struggling. But, like many schools, we had been coaching our children in learning to learn. Pupils were becoming confident enough to make mistakes and more knowledgeable about how to be effective learners. This is where we got the idea to hand the marking over to them.

We came up with a new policy with a few non-negotiables:

- No adult is allowed to mark a child’s book. This means no stickers, no ticks; nothing. Only the children get to write in their book.

- Teachers have to look at children’s books every day and adjust planning as they see fit.

- Every child has to have a conversation (conference) about their learning with their teacher once a week.

In a subject like maths, getting pupils to mark their own work is quite straightforward. Teachers create marking stations or leave the answers on tables, which allows pupils to check their own learning as they are going along. In other subjects, toolkits are discussed with children at the beginning of the lesson so that they can then use them to chart their own progress.

Teachers ‘helicopter’

Children spend a great deal of time “reflecting” on their learning and next steps, sometimes with a teacher during a conference and sometimes with a peer. We often provide sentence stems to support them with this.

In lessons, teachers are encouraged to “helicopter” - to circulate around the class, responding to children’s misconceptions as they happen. To use a Great British Bake Off analogy: we do not want to be like Paul Hollywood, knowingly smiling as bakers make obvious mistakes and then criticising them later for having soggy bottoms. Instead, we want to intervene at the point of misconception.

Staff have warmed to the new system, though it has been a steep learning curve. Some more experienced teachers found the change quite challenging - a few even likened it to losing their right hands. But the NQTs didn’t know any different.

Children, however, universally love it. “It’s so much better now teachers are not writing in my book - it’s so much neater,” one pupil told me. Another said: “It’s my book. It feels like part of me.”

Pupils take more pride in their written work. Outcomes are better and, without the clutter of teacher marking, it is easier than ever to see progress.

As for improving teacher workload, the signs are good. Teachers are going home earlier, suitcases are now used for their proper purpose of packing for weekends away and staff surveys indicate lower levels of stress. It’s also no coincidence that we had fewer teachers leave last year.

The really good news is that other schools are asking to know more about our approach. We have started running conferences to share what we have learned. There is still work to do to fix the workload crisis, but if more headteachers adopt policies like ours, perhaps I won’t warn my daughter off the profession just yet.

Matthew Kleiner-Mann is executive headteacher of Brimsdown Primary, Churchfield Primary and Lavender Primary schools in Enfield, North London

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and Instagram, and like Tes on Facebook