Why teaching still has a diversity problem

Four weeks into his tenure as education secretary, Nadhim Zahawi was speaking at the NAHT school leaders’ union conference when he was asked what he thought about the diversity of the teaching profession in England.

His response was clear: “I want us to make sure that we continue to encourage more Black and ethnic minority candidates into the profession,” he said.

For some, it would have felt like a typically political statement: claim the situation is improving (“continue to encourage”) when it was doing nothing of the sort. After all, calls for more Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) representation are frequent and the frustration of many BAME teachers at a lack of action from the government to tackle this issue is growing.

But whether Zahawi realised it or not, his claim that progress was in motion actually holds some truth.

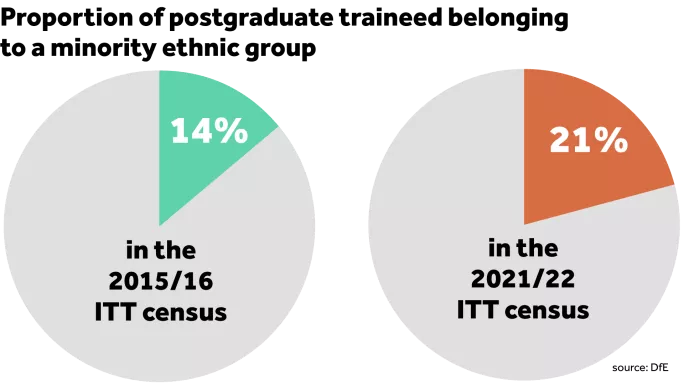

A few months before that speech, the latest Initial Teacher Training Census data from the Department for Education (DfE) revealed that 21 per cent of postgraduate trainees declared they belonged to a minority ethnic group.

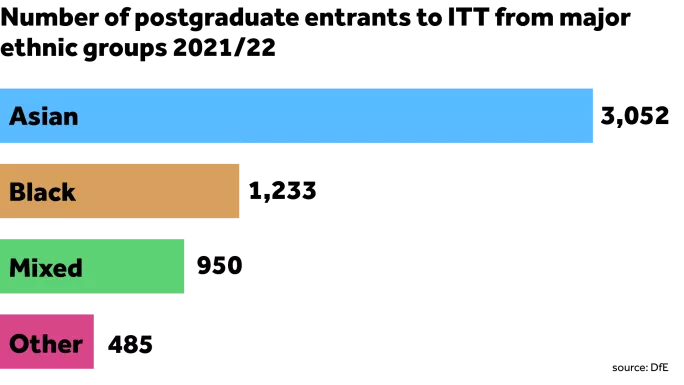

In real terms, this meant of 27,713 postgraduate trainees in the 2021-22 academic year who declared their ethnicity (from an overall total of 31,233), 5,720 said they were from an ethnic minority background, broken down as follows:

- Asian ethnicity: 3,052

- Black ethnicity: 1,233

- Mixed ethnicity: 950

- Other ethnicity: 485

The data marked six years of growth in ITT diversity data, having risen by around a percentage point each year since the 2015-16 ITT census, when it was just 14 per cent. It’s a notable rise and the DfE is claiming much of the credit.

It says it “made diversity a feature” of its recruitment and retention strategy three years ago, and it is “investing in programmes that support all teachers to develop and progress their careers”.

Of course, that alone hasn’t shifted the situation. Elsewhere, numerous teacher training institutions have publicly discussed efforts they have made to improve diversity in their ITT offerings, such as Ark Teacher Training, Manchester Metropolitan University and Teach First.

And Emma Hollis, executive director of the National Association of School-Based Teacher Trainers (NASBTT), says school-based training providers, and her own organisation, have undertaken a “renewed focus” on racial inequality to boost BAME recruitment over the past few years.

“We’ve made diversity and inclusion a key part of our past two annual conferences, with speakers on the topic and masterclasses for teacher trainers with diversity specialist Hannah Wilson,” she adds.

Katrin Sredzki-Seamer, director of the National Modern Languages School Centred Initial Teacher Training (SCITT), agrees that work in this area has become a priority in the past few years.

“We have looked at our marketing materials, application and interview processes, and in-training support to ensure that trainees from BAME communities - and, indeed, also our foreign nationals - are supported and their needs are considered and addressed.”

Ann-Marie Bahaire, director of ITT at the Surrey South Farnham SCITT at South Farnham Educational Trust (SFET), says they are also seeing focus on this area starting to have an impact.

“We’ve tried to increase [our BAME recruitment] because our average over the past few years was five or six per cent [of intake], which is really low compared to nationally, and our current cohort still follows that trend.”

“But our [BAME] recruitment for 2022-23 has increased to 13 per cent, which is quite pleasing.”

All this suggests that there is not one single cause for this rise but rather that a raft of initiatives across the sector have combined to drive diversity over the past six years. Not only that but, if the data from the likes of SFET is replicated elsewhere, we could see another year of growth in this area of ITT national data for 2022-23.

Numbers only one side of the story

So, is it just a case of sitting back and watching diversity in our schools improve?

Not quite. Because while the data sounds positive, some are wary of putting too much stock in it.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that things are getting better in the sector,” says Dr Malcolm Cocks, an English teacher who is head of inclusion at St Paul’s School and set up the Black Teachers’ Network within the African Caribbean Education Network (ACEN).

He notes that the economic disruption caused by the pandemic has to be considered within the ITT numbers for the past two years.

“There’s a scarcity of reliable jobs and teaching is a profession that offers some security,” he adds.

This is certainly true, with overall ITT data showing a huge surge during the pandemic years before declining rapidly, according to the most up-to-date data - which may mean that the diversity figures will drop again.

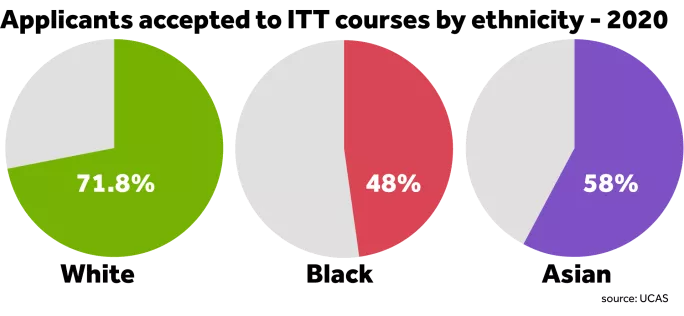

Meanwhile, Sufian Sadiq, director of teaching school at the multi-academy Chiltern Learning Trust, points out that, despite the growth in the numbers of applicants from ethnic minority backgrounds to teaching courses, this group is still not accepted at the same rate as white prospective students, nor retained and promoted in the same numbers.

“When you look at the numbers of people from different backgrounds who apply, then look at who gets on to and completes the course, then who moves up through the career ladder, proportionately, it is still not where we would like it to be,” Sadiq says.

“There’s an issue at the very first stage of the pipeline, and so we need to look at how inclusive training providers really are,” he adds.

Data from the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service proves his point: for the 2020 recruitment cycle, 71.8 per cent of white applicants were accepted by training providers, compared with 48 per cent of Black applicants and 58 per cent of Asian applicants.

It’s an issue that Professor Sam Twiselton, director of the Sheffield Institute of Education at Sheffield Hallam University (SHU), recognises, too.

At SHU, “we do not attract as diverse a population as we would like. We do seek to proactively attract diverse applicants but we need to do more,” she says.

Hollis says SCITTs are aware of the need to do more here. “There is a long way to go; we’re all learning and trying to make steps in the right direction.”

Diversity in ITT itself

Hannah Wilson - founder of DiverseEd, and who regularly works with training providers, such as NASBTT, on issues of inclusivity, culture and diversity - says providers need to look at their own diversity and the message it sends out.

“If we think about who runs SCITTs, most are [run by white women] and the tutors, lecturers and mentors tend to also be white women. So, we have a strong typecast of who does teacher training.

“We really need to disrupt who’s actually heading up teacher training.”

“And then if you haven’t got a very diverse team - and a lot of the SCITTs I’m working with are very aware they’re all white women - how do you then bring in diversity?

“Who’s doing the visiting lectures? Are you just bringing in people from your network who look like you? Which books are you promoting? There are so many different aspects of initial teacher training that can be diversified if we have that intent.”

Pinky Jain, head of teacher education at Leeds Beckett University, agrees that this is an important point.

“Having representation within our own management - I’m a person of colour - makes, I think, a little bit of a difference when students can see themselves in that role coming from those communities,” she says.

All those spoken to agree that this matters so much because, despite the rising diversity in the ITT cohorts, there is still a long way to go to bring the diversity of the teaching profession in line with the general working population, where the last census data (admittedly from 2011) showed almost all ethnicities were under-represented in the profession against wider population data.

Furthermore, the teaching profession is far less diverse than the pupil population, where the percentage of pupils from minority ethnic backgrounds was 33.6 per cent across all school types in the year 2020-21, compared with about 15 per cent of all teachers.

There’s also evidence that BAME teachers are highly concentrated in certain schools - skewing towards diverse schools in London, especially - with a 2020 study by the University College London’s Institute for Education finding 46 per cent of UK schools have no BAME teachers at all.

Finally, when it comes to senior leadership, the picture is well known and stark: only seven per cent of headteachers and 10 per cent of deputy and assistant heads do not come from a white British background.

Back to the start

There is a lot here to unpick but, for Cocks, a lot of this disparity in the data can be tracked back to ITT and the experiences many BAME teachers have as their first engagements with the profession.

“It’s tough for all teachers when you’re on your training programme - for all the reasons that teaching is tough. But it is particularly tough for Black teachers because of racism, isolation and under-representation.”

Sadiq agrees that this is a problem - and often one that can be overlooked by schools and training providers about how a BAME teacher may experience their placement.

“You could be allocated anyone as a mentor; any school or subject coordinator,” he says. “So there’s a lot of goodwill that there won’t be bias throughout that entire process.”

This creates many issues, he explains. “Is there an appreciation of diversity? For example, can a Muslim trainee access prayers? Will they support a trainee teacher who finds they are on a training post where, due to geography, they are the only Black person in the school?

“What education around racial equity and diversity has taken place to prepare the young people that they [the trainee] will be teaching?”

He notes, too, that lesson observations can also be tough and lead to a situation where a trainee feels isolated: “I know some young teachers whose confidence is affected in the classroom by the fact that they have a different accent - if English is their second language, for example,” adds Sadiq.

Wilson agrees that these can be major issues: “If they [the trainee] are working with a mentor who has unconscious bias or doesn’t know what you need to take into consideration when you are [working with] a Muslim person, for example, that’s a real training gap.”

This issue was outlined by a trainee teacher in recent guidance from the Institute for Education at UCL on how schools can support the retention of minority ethnic teachers.

“What was put in place for my training was different from others because I was the only Black person. It ranged from, ‘We can’t understand you because you speak very fast’ to ‘Our students are very impatient. You need to learn how to adapt to their environment’,” they said.

Adapting to avoid issues

So, what are providers doing about this? Sredzki-Seamer, at the NML SCITT, says they work hard to try to place BAME candidates in the right settings - which, she says, has proved successful.

“The heritage of a trainee is considered when we place them in schools, and we have had very positive feedback from trainees who were placed in schools that had little diversity.”

A trainee in London with the NML SCITT agrees that this has worked for them, noting that although they were “worried I was going to encounter some difficulties because of my BAME background”, this proved not to be the case and they felt welcomed by staff and students.

Telma Dias de Brito, another recent graduate, also says she never experienced issues during placements or since she started working: “No one has ever treated me differently because of my origins and colour.”

Sredzki-Seamer is honest, though, that this does not work out every time: “That is not always the case and I do know that BAME trainees can often feel isolated.”

Meanwhile, Bahaire, the director of ITT at the Surrey South Farnham SCITT, says they try to address this potential concern by giving a trainee a choice of options for their placements.

“Placements for trainees are really important and so we think of it a bit like speed dating, where they go to two or three schools and get to meet people there so they get an idea of it all - because it’s a really hard year if you get it wrong.”

Trainees agree, with several telling Tes that the chance to get a feel for a school and pick one that seemed to suit them best made this aspect of their course that bit less daunting.

Bain, at Leeds Beckett, notes, too, that course providers have to ensure they are on top of this and set out to schools what they expect in terms of providing a safe and supporting environment.

“At the very beginning of a school saying, ‘We’d really love to have your students’, we’ll say, ‘OK, let’s talk about our values and what we would expect from the get-go’ - so we work with schools quite substantially on that.”

She admits this doesn’t mean everything is perfect and “sometimes things do go awry”. While they are then resolved, generally, a proactive approach means this happens less frequently and creates a culture where all partner schools understand what is expected of them.

Jain says this is key because, over time, it has to be the case that all settings are inclusive - not that there are some known to be welcoming and others that are not, and training providers end up with two types of school they engage with.

“What we don’t do, and I don’t think we ever will, is go ‘that school’s a good school for a BAME student and that school isn’t’,” she says.

“I don’t think that that works for me, on principle, because every school should be good for everybody.”

The need to do more

Overall, it’s clear that the ITT sector is working proactively to tackle the sort of issues outlined above and, given the rising data is, broadly, making progress.

But could more be done to push this further? Given that, at present, there is a major ITT market view underway, could it be that the government - pushed by Zahawi, perhaps - demands even more of providers to boost the diversity of their intake?

Surprisingly, it seems not, with the government’s response to the ITT market review last December only mentioning the word “diversity” three times in its 70 pages.

“We strongly agree with the views expressed around the importance of diversity in ITT,” was about the most notable line - which at least is a positive view.

Twiselton, who was involved in the original market ITT review, said she hoped the government would seize the window of opportunity that the review presented to do more in this area.

“The market review [is] certainly an opportunity for the DfE to work proactively with providers on this in the planning phase,” she says. “Stage 2 of the accreditation process would be an ideal vehicle for doing this.”

Certainly, given the rising ITT data on diversity, it would seem the right time to build on this and no doubt the government will look favourably on those that can point to good diversity and outreach work.

Yet even if the rising ITT diversity and work being done to ensure school placement experiences are positive, it will count for nothing if the teachers then go out in the wider market and encounter issues of racism, bias and isolation, which, sadly for many, is what happens.

“Discrimination based on race is one of the more significant and deep-rooted factors that affect the experience of teaching and career progression for BME teachers,” a major National Education Union report said in 2016.

Meanwhile, Dr Antonina Tereshchenko, a lecturer in education at Brunel University London who led the UCL research into diversity in British schools mentioned above, said the research revealed that teachers from ethnic minority backgrounds often face “subtle racism and micro-aggressions, which ultimately amounts to an additional hidden workload” when they start working.

She said that many interviewees she spoke to talked about how, even if they didn’t experience racism targeted directly at them, they experienced something termed “environmental racism”.

That could mean observing racism towards students, fearing the label of being “difficult to work with” when calling racism out, or working in a school with a virtually all-white leadership team, even when staff at the school were generally diverse.

An ITT trainee told Tes they are already aware of this: “As a BAME [teacher] with English as my third language, I do tend to keep quiet and just get on with things before I complain.”

All of this, Tereshchenko explains, is challenging for new teachers. “It’s off-putting for young recruits from BAME backgrounds” and means they end up “expending significant psychological energy” to deal with these issues.

Indeed, Tereshchenko’s research points to a 2018 DfE study finding that there are lower retention rates for ethnic minority staff after one year and after five years in teaching.

Specifically, 17 per cent of BAME teachers leave after one year, compared with 14 per cent of white teachers, and 35 per cent of BAME teachers leave after five years compared with 31 per cent of white teachers.

The London effect and early career journeys

This report also notes that BAME teachers have higher retention rates in inner and outer London than white candidates because more BAME teachers work in the capital than in the rest of the country.

This may sound positive but Gary Mullings, head of Vyners School in Uxbridge and co-chair of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL) BAME Leaders’ Network, says it actually means retention rates are likely worse than they would otherwise be.

“You can find that, for some people from diverse backgrounds, they start their careers in challenging schools in big cities,” Mullings says.

“And while some people really like working in these schools and it’s absolutely for them, for others, a challenging context can mean the job doesn’t feel as appealing.”

“If you start your career in a school with a difficult Ofsted rating, for example, then the senior team will be putting a lot of pressure on staff. That is actually not a great place to be as a young teacher joining the profession.”

Tereshchenko’s work supports this with the conclusion to her research saying it was an area that needs prioritising: “As BAME teachers tend to work in urban schools with high-minority and more disadvantaged pupil intakes, it is crucial that government resources are put into their retention.”

However, given that in 2020 the government actually cut money from its equality and diversity fund, this seems like an ask that might go unfulfilled - and is why many in the sector are taking action themselves to try to boost early career support for BAME teachers.

Solving the problem from the frontline

For example, Cocks, as part of work with the ACEN and The Black Teachers’ Network, recently undertook a research initiative called 100 Black Teachers, with the aim of talking to 100 black teachers about their experiences via focus groups and survey questions (the number responding has already surpassed that).

This research is still ongoing but Cocks emphasises that part of its purpose is to help find solutions to the sorts of issues mentioned above when new teachers enter the profession.

One of the clearest calls for help has been around putting together a mentoring scheme that aims to support black teachers specifically across ITT and into their two-year Early Career Teaching framework.

Cocks explains that this would supplement any “formal” mentoring to help give BAME teachers someone to talk to who may have experienced the same issues that they are encountering.

“It would not be someone who has oversight of their qualifications but someone separate, who might be able to offer advice, the chance to talk through any issues or, if there are cases of conflict, help with mediation that is needed.”

“This would require a collective effort - volunteers from across the sector, who may take on a mentee and see them through experiences,” he says.

Mentors would be trained and supported by ACEN, he says, adding that the network is planning to start a pilot of the programme at the second annual ACEN anti-racism conference in September to bring this plan to life.

Mentorship is already seen as a good way to boost ethnic minority talent in the career pipeline, with several mentorship networks aimed at supporting BAME teachers launched in the past few years - often led by current or former Black or Asian educators who reached senior leadership.

These include the BAME-ed Network, founded by headteacher Allana Gay in 2017; Aspiring Heads, an online leadership programme for Black educators; the leadership consultancy Stepping into Leadership, run by former headteacher Diana Osagie; and Mindful Equity, which aims to encourage more Black and Asian women into the profession.

These are all notable initiatives but Cocks and others note that the reliance on mentorship systems also means BAME teachers face an additional burden of having to “not only navigate racism in schools but also to solve it”.

It’s a point that Evelyn Forde, the headteacher of Copthall School in north London and vice-president of ASCL - and who also founded the BAME Leaders’ Network at ASCL before handing over the reins to Mullings - makes, too.

Showing BAME teachers the way to the top

“It is a lot of pressure and it does take time, without doubt, but if we don’t do it, it doesn’t feel like anybody else is doing it,” she says.

However, she believes there is no other choice as, without this work, the risk is that more BAME teachers will be put off the profession or struggle to see a career path ahead of them - aspects she says are key if more BAME teachers are to make it into senior leadership positions.

“It’s important that we set up these networks, and make the effort to be mentors as senior BAME teachers, so that new people stay - because if you don’t see it, sometimes you think you can’t become it or you don’t believe that that’s possible,” says Forde.

Getting visibility at the very top of the profession isn’t just something leaders like Forde, and those running mentorship networks, like Mullings and Cocks, want to see either.

If we return to the conference appearance last year by Zahawi, he acknowledged that diversity in leadership needs to be improved: “School leadership is not representative when it comes to race,” he said. “There aren’t enough black headteachers.”

Forde says this was important for him to say. “The education secretary has made this bold statement and it’s great to acknowledge it.”

But, if the government is serious, ministers need to “put their money where their mouth is”.

This is something, she says, could be done by bringing back the equality and diversity funding that was pulled in 2020: “Let’s start reinvesting and investing in specific training and support so that there is a clear pathway to leadership for people of colour.”

Again, like Cocks, Forde is not waiting on the government to solve this but is, instead, proactively trying to solve some of the leadership issues that can prevent more BAME candidates from reaching the top.

One big issue is around appointing panels, which she says often comprise “white men in suits who see it as a risk, potentially, to appoint somebody who doesn’t look like them”.

It’s an issue Forde experienced first-hand, noting that she often applied for deputy headships and repeatedly heard she was, “just not the right fit” in interview feedback.

To try to tackle these issues, ASCL has teamed up with the National Governance Association (NGA) to offer free anti-racial bias training to governors that will go live in April - something NGA chief executive Emma Knights says the organisation knows has to be improved.

“There are many topics that new governors and trustees must have knowledge of, but equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) is one which can be difficult for boards and leaders to know where to begin,” she says.

“Along with ASCL, we identified the need for some universally available training for governing boards on EDI some time ago.”

The intention, she says, is to provide help “for all schools and trusts to address these issues if they have not yet begun to”.

As noted earlier, UCL’s Institute for Education has also published guidance for school leaders about how to support BAME teachers, which outlines many of the same issues identified above and has been developed in conjunction with ASCL.

This document contains a raft of ideas - from simply being open to acknowledging and discussing issues of race and racism in schools, to avoiding tokenism in hiring practices. Another key point it makes is to be more objective about appointing and having career paths for BAME teachers.

“Teachers from minority ethnic backgrounds are more likely to stay in teaching if they are well supported in the early phase of their career to understand and navigate the predominantly white profession,” it notes.

Better talent management

As such, the guidance says schools should be “proactive in spotting and nurturing talent among [BAME] staff members” rather than expecting it to happen organically - as the data outlined above shows that this often does not happen.

Mullings, at Vyners School in Uxbridge, agrees that this is important because, too often, the “informal” nature of career pathways can work against BAME candidates.

“What the underlying issue often seems to be in education - and I think education is a bit behind some other sectors in this - is there’s a lack of objectivity in a lot of these processes,” he says.

“I know as a manager that when you’re discussing who might be good for which pathway, for example, a lot of the discussions are anecdotal; it’s not following an objective methodology.”

Forde concurs that this free-form approach to talent spotting can be an issue - and can result in bias creeping into school career pathways.

“For black people, in particular, we get pigeonholed into behaviour management,” she says.

“It’s seen that you’re probably good at walking corridors and behaviour but are you good at strategy? Are you good at curriculum? Lots of people don’t get the opportunity to try because they’ve been pigeonholed early on.”

Mullings adds that this kind of bias - often subconscious rather than overt prejudice - can take its toll on BAME staff, especially if attempts to climb the career ladder are rebuffed.

“If you come up against these challenges throughout your life, you do question yourself, you say, ‘Is it me? Or is there something happening that is problematic?’”

Yet, despite these concerns, Mullings says he is aware there is “really good work going on” across the sector to address the issues BAME teachers face at all points in their careers. It is vital this work continues and the sector continues to recognise the issues it needs to tackle, he adds.

“It’s about being brave enough to take the right steps to make sure that a lot of the barriers for new cohorts are actually removed.”

Jain, from Leeds Beckett, concurs and says the hope is that if ITT providers and the sector work to maintain the growth in diversity seen over the past few years, and schools improve their work to welcome these teachers in - and then provide meaningful career progression - the ongoing growth in diversity and equality in education that Zahawi wants to see will start to move in the right direction.

She adds: “It’s about having those conversations early and empowering everyone within the system to think ‘I belong’.”

Dan Worth is senior editor at Tes, Helen Lock is a freelance journalist

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article