‘Winter of Discontent’ comparisons undersell teacher pay woes

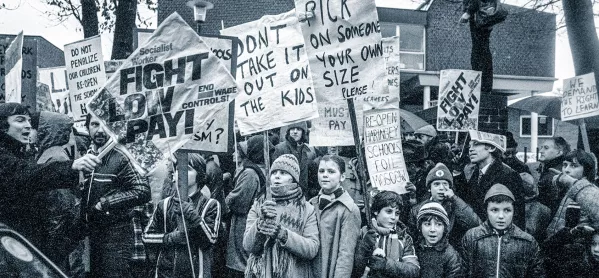

Talks of general strikes have evoked numerous claims that we are due a 1970s-style Winter of Discontent that will see workers across sectors, including education, strike for better pay in the face of the rapidly rising cost of living.

Yet for the modern teacher, the 1970s is perhaps an era that has much to recommend it - not least the 1974 Houghton report, which said teachers should receive pay increases averaging 27 per cent.

What’s more, a graduate entering the profession in 1978 on the main pay scale (MPS) at point 1 would earn between £2,964 and £4,662 - moving up an MPS point each year.

Even with house prices quadrupling between 1970 and 1979, from £4,057 to £19,925, a mortgage was eminently affordable.

But by 2021, teachers’ starting salary was £25,714 and the average house price was just over £270,000, effectively blocking many teachers from access to mortgages and leaving them trapped paying monthly rents, which were often higher than monthly mortgage repayments would be.

In that same year, a report by the Institute for Fiscal Studies, titled The long, long squeeze on teacher pay, concluded that “unless salaries for more experienced teachers grow by 13 per cent in cash terms over the next two years, they will still be lower in real terms than in 2007, which would still be a remarkable squeeze on pay over 16 years”.

Furthermore, a teaching career path will almost invariably lead to a lower-paying career, as teachers’ salaries now lag 8.2 per cent behind comparable graduate professions.

As such, the threat of strike action now is less about protecting a salary that would be higher than the white-collar average, as it was in the 1970s, than helping teachers to cope with a cost-of-living crisis that has left some dependent on food banks.

Pensions and private schools

It’s not just take-home pay that has been eroded: teachers’ future financial security has been hit hard.

Pensions are deferred pay, which is saved into a scheme to fund retirement when employees are no longer fully or actively employed.

For many, it would have been a distant compensation to realise that the erosion to their annual salary would be partly compensated for by the advantages of being in the Teachers’ Pension Scheme (TPS).

However, that security has also been diminished by successive governments, particularly between 2010 and 2022.

In 2013, teachers’ contributions rose so that those on £21,000 a year paid an additional £103, while those on £35,000 paid an extra £341.

Then, in 2015, new teachers were enrolled into what the pensions industry rather disingenuously tends to refer to as a “CARE structure” - an acronym of “career average revalued earnings”, which is much less advantageous than the final salary scheme.

And in 2019, the government decided that employers should pay in more, rising from 16.48 per cent to 23.68 per cent in September 2019.

Currently, a government grant covers the extra burden for the maintained sector but employers in the independent sector have to pay the full sum. How long can this be sustained in the current economic climate? And what will the impact be on employment in state schools?

Meanwhile, almost a quarter of independent schools, faced with a 43 per cent rise in their employer contributions, have already left, or are considering leaving, the TPS and have offered their staff a cheaper scheme with reduced benefits.

This hits new teachers particularly hard and is likely to adversely affect recruitment in independent schools, more so than in the maintained sector - at least until the government grant is withdrawn.

Ever-growing workloads

Of course, teachers don’t do what they do just for money - a huge percentage are driven by the love of the job, by its calling, by the unquantifiable joy it can bring.

Yet that, too, is being eroded by ever-rising workloads, increased accountability, reduced funding and poor wellbeing.

This was made plain in recent Talis (the Teaching and Learning International Survey) research that showed English teachers are at the top of the high-workload league among European teachers, and fourth out of 48 countries worldwide.

Perhaps, then, it is no wonder that the government has finally woken up to the need to fix the “leaky pipeline between training and entering the classroom” to tackle the “low retention rates [which] mean almost 20 per cent of newly qualified teachers have left the profession within their first two years of teaching, and 31 per cent within their first five years”.

This focus has included the laudable intention to give “a £30,000 starting salary for all new teachers”. Yet this was done, in part, by minimising pay increases for senior and experienced teachers to a figure well below inflation.

What’s more, with the rapid inflation being seen across the economy, even the boost to new starter salaries will not have the desired impacted on recruitment and retention - as a recent NFER report made clear.

So, while the threat of national strikes may be suggestive of another Winter of Discontent - and the economic and social upheavals which that caused may be generating headlines - the long-term impact of a national teacher shortage on the economic and social growth of the country could last a lot longer.

A recession may offer a boost to recruitment, as Sam Freedman noted recently in Tes, but as a long-term strategy, something more substantial is needed.

Yvonne Williams has spent nearly 34 years in the classroom and 22 years as a head of English. She has contributed chapters on workload and wellbeing to the book, Mentoring English Teachers in the Secondary School

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article