- Home

- What if all edu-policymakers worked in the classroom?

What if all edu-policymakers worked in the classroom?

My disco-kipping days are back. When I was a proper teacher, in the 1990s, and a semi-proper disco-kid, too, I had to sleep for at least two hours on Friday evening, before I could drag myself anywhere. My girlfriend used to wait - usually patiently - for me to recover from 30 hours of 30 Year 5s.

Now I am back teaching for a cursory but salutary day a week. On Thursday evenings, I put away my strategy-saturated laptop and get to bed before the 10 o’clock news. First thing Friday, I cycle to a large local primary school.

In the morning, I cover subject leaders’ PPA time. After lunch, I’m with an excited Year 2 class in an amazingly stocked D&T room, teaching them more than I really know about wheels, axles and chassis.

After that, I’m straight to bed, though not, generally, to prepare myself for a nightclub - a Friday-evening bottle of wine is enough these days.

Out of touch with schools

I’m an education consultant, working part-time for a charity. After almost 20 years away from the classroom, I have found a school that has taken a risk with a regular Friday PPA gig for me.

During these decades, I’ve probably visited over 100 schools, and spent time in meetings or CPD sessions with thousands of school leaders, teachers and pupils.

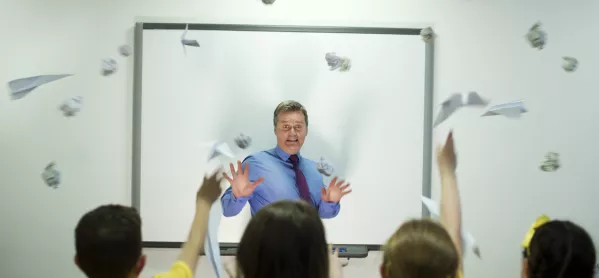

But all these experiences are dangerously removed from that moment when 60 young eyes are on you, waiting for you to command their attention, or looking for opportunities to avoid your attention.

I’m struggling with the spelling, punctuation and grammar, although I’m often impressed by how these rules are improving kids’ writing. Every lesson, I need to appoint a whiteboard monitor to help me break my luddite ways. But behaviour management has come back relatively quickly: generally, primary school children seem calmer and more compliant than they were in the 1990s.

Back to the chalkface

I finish every Friday asking myself various ill-formed questions about practice, all of which I’m careful not to share in the staffroom.

How can freeform play-based learning, unless very skilfully managed (so: not by me), avoid exacerbating existing word gaps between social classes? How can direct instruction and wait time be tailored to be challenging enough for most children most of the time? What, if anything, can be done about the way that girls and boys from some communities appear to segregate from each other from the age of 9 or 10? How many gluesticks do our 20,000 primary schools get through in a year?

Perhaps every adult whose job aims to influence the way in which schools do things should spend at least part of their year teaching. From academics to policy wonks, civil servants to union officials, programme leaders to edtech evangelists, you’d all have much to learn and a little to offer.

If, like me, you are in the “pool of inactive teachers” (the PIT), dust off your qualifications, find a willing supply agency or school, and encourage your employer to grant you the time - a day a week, a week a term or whatever suits.

From small screens to big whiteboards

The recent, welcome Department for Education-led attempts to improve flexible working, while rightly focused on retaining those in the profession, could also find ways to encourage schools to take on those of us whose time teaching will be limited and irregular, but who bring professional experiences that might add a different kind of value.

I know how busy we all make ourselves, rendering the idea of a fifth of our time being spent elsewhere impractical. But some of our new generation of opinion-formers are sending hundreds of tweets a week and probably reading thousands. Many of this cohort of tweeters have never taught.

I don’t deny their right to their current livelihoods, or their aspirations to inform education policy and practice. Perhaps if they dedicated some of their small-screen time to the big whiteboards in classrooms, they would both discover and contribute more than social-media activity could ever enable.

Aside from clubbing, the other activity I stopped doing so regularly as the 1990s wore on was watching Arsenal. I got fed up with all those moaning fans, appalled by anything but a perfect clearance, pass or shot. If they had ever played football, they had clearly forgotten how difficult it was to do even the simple things well, especially at pace.

I deserve no plaudits for my paltry five hours a week in a classroom. But perhaps our schools deserve a set of policymakers and shapers who, through a regular, deep engagement with the act of teaching, might be more careful in their critiques and exhortations.

Joe Hallgarten is an education consultant and a (very) part-time teacher. He tweets as @joehallg

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters