Grammars jump before they are pushed to take the poor

It has been one of the best-known names in Merseyside education for more than three centuries.

The Liverpool Blue Coat School is so long-established and revered that some assume it’s an independent school - despite being originally set up to educate poor children.

But now this top-performing state grammar school is making a concerted effort to reach out again to some of the most disadvantaged families in the city.

From September next year, the school will lower its entrance exam pass mark for up to 27 pupils eligible for free school meals (FSM), to encourage an increase in the number of poorer children it admits.

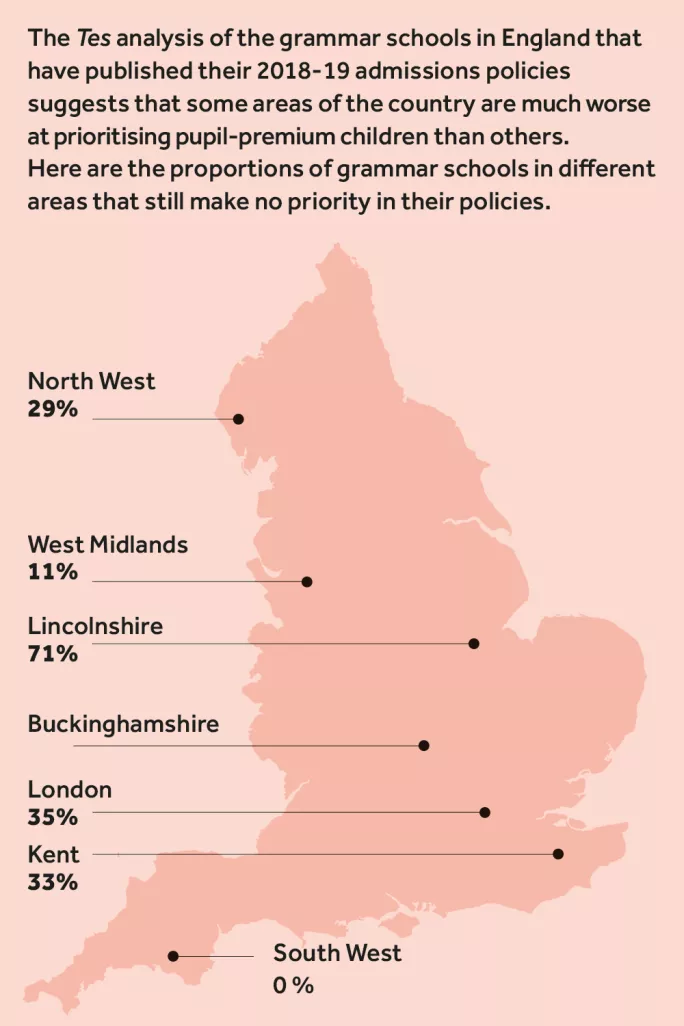

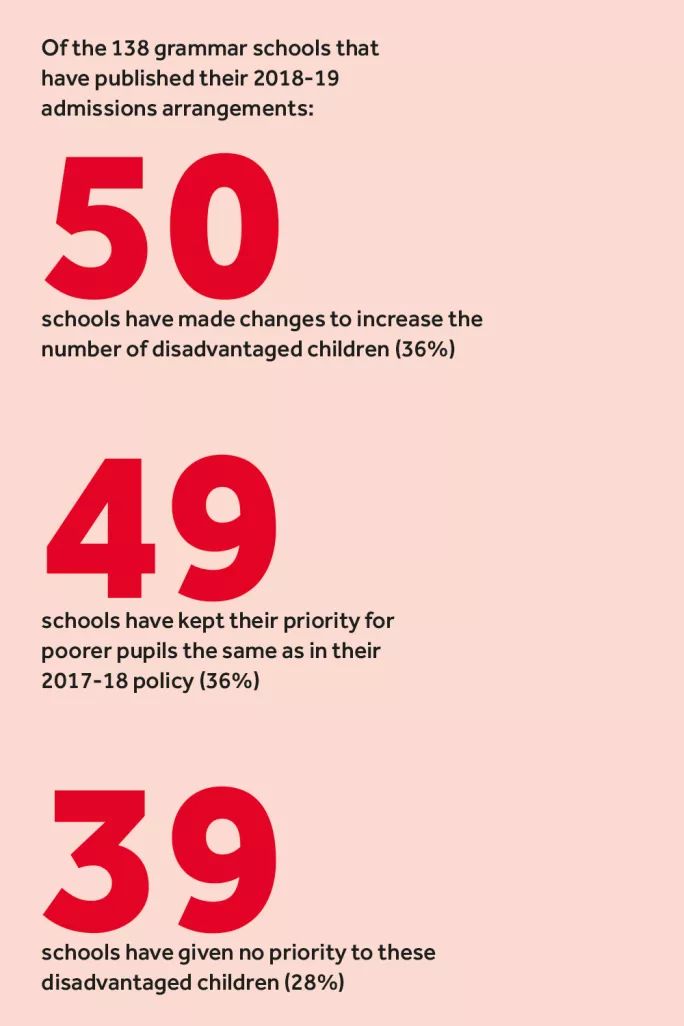

And Blue Coat is not the only selective school making changes to help tackle social mobility. Our new analysis suggests that at least 50 grammar schools across England will alter their admissions procedures in 2018 in order to take more children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The changes follow the government’s unveiling of plans to force existing selective schools to become “representative of their local communities”. But many grammars are opting to do something now before any new rules are introduced.

More than a third (36 per cent) of the existing grammar schools that have published their admission policies for 2018-19 will give poorer pupils some priority for the first time, or will further relax entrance requirements for these pupils.

Only a minority of England’s grammars took into account a child’s eligibility for FSMs in their admissions policies for this September. But our analysis suggests that by 2018 almost three-quarters will give some degree of priority to disadvantaged pupils.

However, behind that figure there is a huge amount of variety. And simply adding these pupils from poorer homes to a school’s oversubscription criteria may not make much difference to admissions in practice.

The pupils would still have to secure enough marks to pass the entrance test before they are considered for a place - and many of these disadvantaged children will already be behind their privileged peers academically.

Making an impact

So some selective admissions policies that have been billed as promoting social mobility may, on closer examination, be unlikely to have a significant impact.

There has also been some delay. Schools have been able to prioritise the admission of pupil-premium pupils since the current school admissions code came into force in December 2014.

But the majority of grammars did not do this as soon as they were allowed to. So why are these selective schools changing their admissions policies now?

The pressure to be more socially inclusive has been rising since September when the government announced its plans to expand academic selection and make existing grammars more “representative”.

Critics of the plans have focused on the low number of FSM pupils currently attending grammar schools.

Research from the Sutton Trust social mobility charity shows that less than 3 per cent of grammar school pupils are entitled to FSMs, compared with an average of 18 per cent in the areas they serve.

To address this disparity, the government wants to require all grammar schools to prioritise poorer pupils in their oversubscription criteria. And there is plenty of room for change. Of the grammar schools with published admissions policies for 2018-19, 28 per cent still will not give any priority to these pupils.

The government’s Green Paper on expanding selection says: “Selective schools also need to ensure that the pupils they admit are representative of their local communities.

“We need to increase the pace at which selective schools are ensuring fair access. We therefore propose to require all selective schools to have in place strategies to ensure fair access.”

It goes on to warn that: “Legislation would require selective schools to prioritise the admission of, or set aside a number of specific places for, pupils of lower household income in their oversubscription criteria.”

It takes around 18 months to alter an admissions policy, so 2018-19 is the first academic year for which schools have been able to respond directly to the Green Paper. And doing so doesn’t necessarily demonstrate a genuine commitment to social mobility.

One admissions officer at a grammar school that will prioritise children registered for the pupil premium for the first time next year admits that the school only made the change because of the ministers’ agenda.

“We have to be seen to be incorporating it,” she says. “There is certainly the political pressure to do it and the government wants grammar schools to do more for social mobility. Our headteacher is very involved in networking so it’s obviously coming from the government.”

Grammar schools could still find themselves being forced to go further in improving access for poorer pupils than they have been prepared to do voluntarily.

According to a government source reported in The Times this month, existing grammars may be required to offer lower 11-plus pass marks to poorer children. Currently only a handful of schools do this.

‘Massively important’

But at the Blue Coat School, head Mike Pennington insists that the school’s decision to lower its FSM entrance test pass mark is not linked to government pressure. The school began developing the plans before Theresa May became prime minister.

“Social mobility in Liverpool is a massively important thing for us to tackle and to face up to, and to be prepared to try things that are going to change it,” he says.

Currently fewer than 10 per cent of the school’s pupils are eligible for free meals - a significantly lower proportion than the Liverpool average of around 45 per cent.

What remains to be seen is how much of a difference altering the pass mark will make. For many grammars, getting poorer pupils to take the test in the first place - especially if they do not live nearby - can be a greater challenge than getting them to pass the test.

“We know there are students in the city of Liverpool who could consider coming to Blue Coat but don’t,” Pennington says.

“Too often, this can be influenced by myths about what our school is and who it is for and what kind of people thrive here.”

Lawrence Sheriff School, a grammar in Rugby, is also making changes. In 2018 it will take up to 10 disadvantaged students who score 20 marks lower than the automatic qualifying score in its entrance test.

That is a relaxation from September this year, when the school will allow up to 10 disadvantaged students just 10 marks leeway. Head Peter Kent admits that it will not be a “magic bullet”. And with a total of 120 pupils in a cohort, its effect can only be marginal.

But Kent insists that it is important for the school to “get the strong message out there and maximise opportunities”.

However, Jim Skinner, chief executive of the Grammar School Heads’ Association (GSHA), believes that scepticism about the possible impact of such a change could discourage some grammars from trying it at all.

“Some heads will look at [altering admissions] and see that giving priority to pupil premium will have little or no effect, so they may be hesitant to change the policy,” he says.

One admissions officer at a rural grammar school admits that prioritising poorer pupils in admissions would not “make the slightest bit of difference” because there are few poor families living near the school - and disadvantaged families further away are deterred by transport costs.

Grammar school heads often see their primary outreach work as more important for social mobility, because it can encourage a wider range of pupils to sit the 11-plus.

But Lee Elliot Major, chief executive of the Sutton Trust, says research shows that there is a general problem with social segregation in schools and that grammars are among the worst offenders (see column, right). He wants them to be judged on how inclusive they are for the areas they serve .

“If we want the school system to help all children, we need to start thinking about how we measure that as a school,” he says. “Before the government expands any more grammars we do need to see if the existing grammars are successful in these new social mobility measures.”

What is already clear is that the majority of England’s grammar schools are keen to be seen to be doing something, before ministers force them to. But whether their changed admissions rules will really alter the social make-up of their schools remains to be seen.

Additional research by Helen Ward and Will Hazell

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters