- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- How one school teaches - and assesses - creativity

How one school teaches - and assesses - creativity

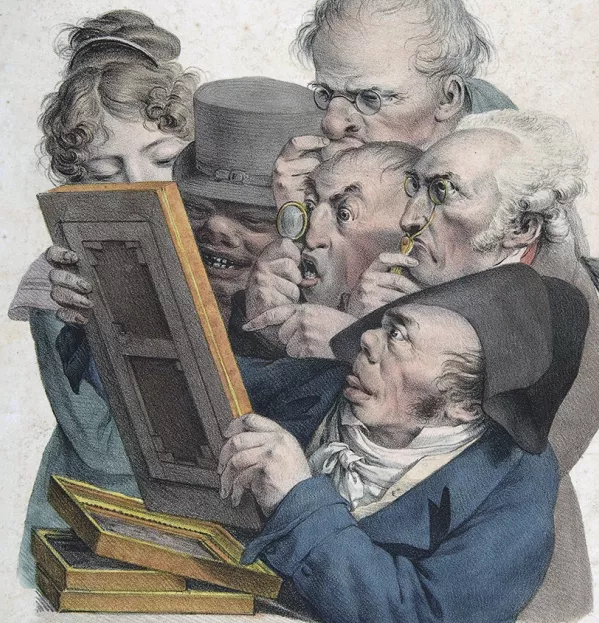

Creativity: the result of a beautiful alignment of the stars, a visit from the muses, inspiration striking like lightning. Or is it? Rather than a mystical, quixotic movement of the soul, could creativity in fact be a structured process? One that could even - gasp - be taught?

At King’s High School, Warwick, Year 10 students now study for a certificate in creativity, and there’s no otherworldly mystery to the success they’re having, say headteacher Stephen Burley and acting deputy head Philip Seal. We caught up with them to find out how their programme works.

Tes: The debate about whether creativity can be taught still rages on. What are your thoughts?

Stephen Burley and Philip Seal: The question of whether schools can teach creativity is far from new. The late Sir Ken Robinson’s 2006 TED Talk “Do schools kill creativity?” - with its 65 million views - helped to kickstart the debate. Over time, many other voices have chipped in to inform our thinking about how what we do in schools nurtures, or indeed negates, the natural creativity of young people.

The debate centres on the idea of creativity as a spontaneous artistic endeavour (in the Romantic tradition of Wordsworth et al) but also as a valuable soft skill for young people in the modern world. Forbes claimed last year that there are five major soft skills that lead to career success, with creativity topping the list (ahead of collaboration, emotional intelligence, adaptability and persuasion).

Now, Pisa [the Programme for International Student Assessment] has announced that it will assess creative thinking for the first time in its global educational rankings from 2022.

So, what do you think are the key things people need to remember about creativity and education?

Creativity is not about coming up with an idea out of thin air. It’s about invaluable real-world skills that will help young people flourish in a world dominated by artificial intelligence: problem solving, teamwork, critical thinking and resilience, to name just a few. Creativity is a foundational intellectual disposition that must be front and centre of any truly valuable and enriching programme of education.

You have come up with a way to explicitly teach those skills. Tell us about the certificated programme you’ve developed.

Over the past two years, at King’s High, we have designed and trialled a Certificate in Creative Thinking for Year 10 students. All students in the year group spend 20 timetabled hours over the course of the year working towards their certificate.

This involves them choosing a real-world problem, conducting structured research into it and then thinking creatively about how that problem might be solved.

Our experiences so far are very clear: creativity can be learned, practised, honed and, indeed, assessed. Discussions are now under way with the New College of the Humanities about the possibility of accrediting the course, and for schools to deliver this nationally and globally.

What are the main challenges of a programme like this?

The challenge for anyone trying to teach creative thinking in a truly effective way is providing students with the structure and scaffolding to think creatively, and hone and sharpen their creative ideas. Without the structure and scaffolding, they will inevitably struggle to come up with their lightbulb moments. But it is utterly clear to us that teaching creative thinking has huge benefits.

What sort of approaches do you use to provide that structure?

We have found that a carefully scaffolded approach to the teaching is the key to success. For example, we introduced the “use X to solve Y” formula and it was a breakthrough. “Y” represents the chosen problem area and “X” the way in which the students will solve it.

For instance, “I will use greenhouse architecture to create a wellbeing restaurant set in an indoor garden” or “we will use biological research to design a human that could live for 200 years”.

This formula immediately invites students to think about how they will apply research when solving their problem, rather than having to conjure up ideas out of nowhere. Instead of blue-sky thinking, which can lack structure and feel dauntingly open-ended, this is a grounded, knowledge-based approach to the generation of ideas.

We also encouraged morphological analysis, which sounds complicated but essentially involves students splurging (to use the technical term) as many ideas as they can into a table.

Once the ideas have been splurged, the process of quality control can begin. Which ideas are realistic, useful, innovative? When you think about individual ideas in more detail, do they spark further ideas or alternatives?

The advantage of this method is that it takes the pressure off having good ideas the first time around and embeds the idea that you will very likely fail (and some ideas will be bad) along the way.

How have students responded?

The response has largely been positive. When we asked students for feedback, one said: “I really enjoyed my project as it gave me the freedom to learn about something that I was personally interested in. It improved my skills in things such as problem solving and my ability to think outside the box.” Another student commented: “While working on my project, not only was I able to develop my analytical skills when conducting research on my chosen topic but I was also given the opportunity to apply a more innovative approach to the problem at hand.”

What has the impact been and what do you hope to achieve through the programme in the future?

Those thinkers who have sounded notes of caution about placing creativity at the centre of education have tended to frame the debate as a zero-sum game, pitting a knowledge-rich curriculum against one that enables the free flow of ideas.

Our experience of teaching the certificate makes clear that this polarity is, quite simply, unnecessary. When students know in advance that their knowledge will be put to creative use, their motivation - and, therefore, depth of learning - increases.

Similarly, the process of generating ideas liberates students from the soulless task of memorising information purely because it might be useful for the test, and enables them to use their knowledge in a memorable and enjoyable way.

Stephen Burley is headteacher and Philip Seal is acting deputy head (academic) at King’s High School, Warwick

This article originally appeared in the 26 February 2021 issue under the headline “How we… Certified creativity”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article