Is a new league table ‘crude’ or long overdue?

Headteachers across Scotland may have taken a sharp intake of breath recently, when researchers published a new “league table” of secondary schools.

The analysis of official figures, in the form of an interactive scatter graph, ranks all of Scotland’s schools according to the proportion of pupils on free school meals against the percentage of students overall achieving a set number of Highers.

The result is revealing - and proves to be very controversial - stuff.

We want to identify the schools that are bucking the trend, that don’t go with the norm, that have deprivation but are doing well academically

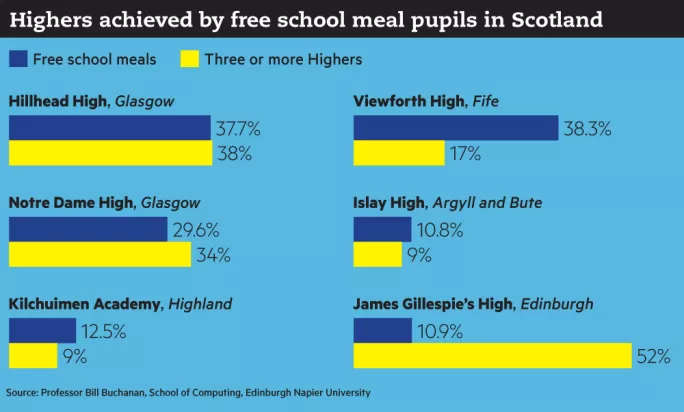

The computer scientists responsible for the table took to Twitter to highlight the “great work” of the school at the top of their chart (Hillhead High in Glasgow), as it appeared to be achieving far better results than others in similar circumstances on this measure.

The school has 37.7 per cent of pupils on free school meals. Yet 38 per cent of pupils in total go on to gain three or more Highers.

Other schools with a similar proportion of pupils claiming free meals do not fare so well. At Viewforth High in Fife, for example, 38.3 per cent of students claim free meals, but only 17 per cent achieve three or more Highers.

The analysis also highlights schools such as Argyll and Bute’s Islay High and the tiny 50-pupil Kilchuimen Academy in Highland. The graph shows that at both schools, around a tenth of pupils are on free school meals but just 9 per cent of all pupils achieve three or more Highers.

However, despite the interest the analysis has sparked on social media and at a recent headteachers’ conference in Edinburgh, fellow academics have criticised it. They claim that the research is “crude”, lacks context and is “potentially damaging” to the schools that come near the bottom of the pile.

The compiler of the analysis, Bill Buchanan, a professor in the School of Computing at Edinburgh Napier University, says that rather than heaping plaudits on schools that receive middle-class pupils and get good results, his league table highlights those that manage to “overcome the problems” in their local areas.

Hillhead High has been particularly successful in this regard, he claims, and is an “outlier” that “overachieves.”

“We want to identify the schools that are bucking the trend, that don’t go with the norm, that have deprivation but are doing well academically,” Buchanan adds.

Taken out of context

However, Sue Ellis, professor of education at the University of Strathclyde, says that, ultimately, data is “meaningless numbers” unless set properly in context.

A school in a rural area, she points out, can look like it is underachieving, but it might be that the pupils just want to learn the basics and then “go and work on the family estate”

Hillhead High, meanwhile, serves a unique catchment area, Ellis says. Located in the West End of Glasgow it has to grapple with deprivation but it also has the University of Glasgow on its doorstep and cannot be compared to schools that serve areas of “grinding poverty”.

“It is not good academic practice to publish intuitively appealing but ultimately incomplete, poorly analysed - and, therefore, unreliable - data as if it were reliable information about whether schools are doing well or otherwise,” she adds. “The public and profession should expect that a university website or Twitter feed offers reliable information and academic rigour with caveats about the information.

“If Scotland is to use educational data well, everyone has to move up several gears in data literacy - educators, parents, the media, politicians and (on this evidence) some academics.”

Highland Council pointed out that Kilchuimen met the needs of its pupils in an “inclusive” way, and provided “a positive and nurturing environment for local children to achieve good attainment over the years”.

Argyll and Bute Council said that the graph did not appear to take the context of individual schools into account.

The controversy around the research has prompted education experts to acknowledge that there continue to be substantial gaps in terms of the data available on Scottish education. There is little to help quantify how well the poorest pupils are served by the system, they say. Particularly frustrating to academics has been the lack of data currently available at primary level.

“The data environment we are in now has not been poorer since the 1960s,” says Lindsay Paterson, professor of education policy at the University of Edinburgh.

Buchanan says that he was motivated to produce the graph by a desire to see more evidence-driven policymaking. He describes last summer, particularly the misinformation that surrounded the EU referendum, as “a disaster”.

He believes that information should be fed directly to citizens in order to allow the general public to make up their own minds, instead of relying on politicians and journalists who, he says, can twist the statistics or simply misinterpret them.

However, Buchanan is guilty of contributing to the poor quality of analysis and debate that the UK has been subjected to in recent months, Paterson insists.

“This is the kind of statistical analysis that was being done in, say, the 1960s,” he says. “Developments in data, techniques and understanding have taken us far beyond such analysis…In short, I would not give this a pass as an undergraduate essay.”

Meanwhile, Dr Ben Williamson, a lecturer in education at the University of Stirling, questions whether it is valuable to compare schools in “such a public way”.

“There could be significant consequences for schools towards the bottom of the graphs and tables if the data was used politically without any deeper analysis or contextual consideration,” Williamson says.

Solving the information deficit

The Scottish government’s plans for a National Improvement Framework (see box, below), and its controversial literacy and numeracy tests, might help to solve the country’s information deficit when it comes to education, Ellis says.

She is optimistic about the NIF’s potential, commenting that it is “neither moral nor smart to let young people work their way through 11 years of education and then say, ‘Sorry it seems the system hasn’t been very fair to you.’ ”

The league tables feared in Scotland were halted in Ireland by removing school-level data from its Freedom of Information legislation, she points out.

Everyone needs to be very careful about presenting numbers in ways that are responsible and ethical, and this means being clear about what the numbers might mean

However, she argues that if Scotland’s newly data rich environment is to be a success, teachers need to be trained in basic data analysis.

“Everyone needs to be very careful about presenting numbers in ways that are responsible and ethical, and this means being clear about what the numbers might mean,” Ellis says. “University academics need to lead the way in this.”

Paterson agrees that the NIF might have potential. But in order to be useful, it will have to capture information about pupils’ backgrounds; raw test results will not be enough, he warns. He also urges the government to share the data collected for the NIF with researchers.

“To make it credible, it has to be made available to independent researchers - that requires trust,” Paterson says. “I hope the government trusts researchers to give them independent access to the data.”

On this, at least, he and Buchanan agree: information on the success, or otherwise, of Scotland’s school system cannot be the preserve of politicians.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters