Revealed: schools’ ‘soul-destroying’ bids to fix broken buildings

Hundreds of schools are repeatedly facing “soul-destroying” rejections in applying for funding to fix crumbling school buildings, Tes can reveal.

School leaders say they are wasting time and resources bidding for funding - only to be knocked back multiple times and left with collapsing roofs and leaking windows.

They describe the process of applying for funding through the Condition Improvement Fund (CIF) - aimed at addressing “significant” need - as a “form of madness” that is delaying crucial work.

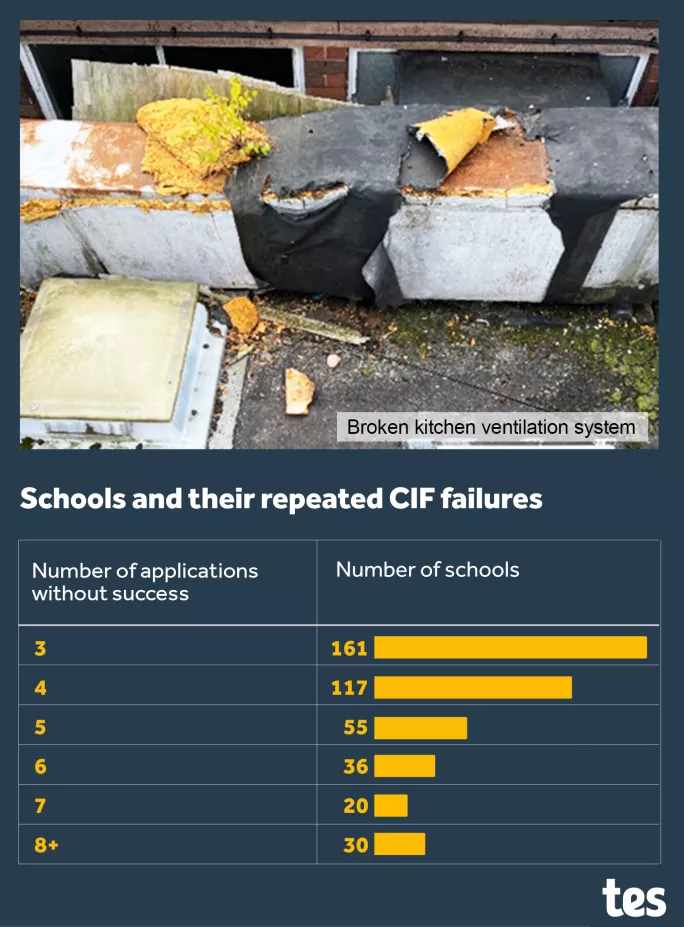

The scale of the problem is borne out in data, seen by Tes, revealing that more than 400 schools have had at least three CIF applications rejected since 2016 without a single successful bid.

And 50 schools have had seven or more rejections without success, according to the Department for Education data, obtained via a freedom of information (FOI) request.

Tes’ investigation shows how the funding process is “failing too many schools”, warns James Bowen, director of policy at the NAHT school leaders’ union.

It also reveals that applications to the fund are not considered entirely on merit, according to school business experts.

CIF funding is open to smaller academy trusts, as well as some voluntary aided schools and sixth-form colleges - meaning there are around 5,000 schools in total that are eligible to apply for the fund.

But a large amount of the school estate was constructed decades ago and needs an “increasing amount of maintenance and repair”, according to Julia Harnden, funding specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL).

The need for more funding

Given that only around 1,400 to 1,500 bids have been accepted per year over the past few years, the CIF process “inevitably results in some buildings that are in urgent need of improvement getting bypassed”, says Harnden.

That many school buildings are in a poor state of repair is undisputed: in 2017, a National Audit Office report suggested that it would cost £6.7 billion to return all school buildings to satisfactory or better condition, and a further £7.1 billion to bring parts of school buildings from satisfactory to good condition.

- School buildings: Half of teachers say school buildings ‘unfit for purpose’

- Funding: The next 50 schools getting rebuilding cash

- Facilities: Why the design of school buildings matters

And as recently as last year, a report by the Department for Education put the cost of repairing or replacing “all defective elements in the school estate” at £11.4 billion.

Harnden says the government “must do more” to increase the capital funding available so that schools are not having to compete against each other to receive cash.

“Seeing repeated bids turned down can be soul-destroying for those involved and, on each occasion, more time passes when the improvement work needed cannot be started and the condition of buildings worsens,” she adds.

While the size of the CIF funding pot could be the reason why some bids are rejected, it does not explain why some particular schools are hit with successive rejections while others are repeatedly successful.

Tes’ data shows that 419 schools have had three or more unsuccessful applications since 2016-17 without a single successful bid.

If schools that have had at least one successful bid are included, 761 have had five or more bids rejected.

Why are some schools repeatedly rejected?

At the other end of the spectrum, there are 534 schools that have had five or more successful applications, while 13 have had 10 or more.

Overall, just under half (46 per cent) of the successful bids since 2016-17 have come from around a fifth of the eligible schools.

The DfE insists that the success of bids is based “solely on need”. So, are successful schools simply the ones that need the most help?

Looking at the bids of schools that are successful again and again, it is clear that they are for genuinely necessary maintenance work, rather than expansion projects.

The school with the most successful bids - 11 - has applied for roof repairs, replacement of its fire alarm system and electrical rewiring, for example.

However, this does not necessarily mean that others’ unsuccessful bids were unworthy of the funding.

Analysing the detail of unsuccessful bids is ultimately impossible because the DfE will not provide the data, saying that publication would “discourage schools from applying” in future - even if school names were hidden.

But, anecdotally, it does appear that many schools with seemingly worthy bids are being rejected.

‘Seeing repeated bids turned down can be soul-destroying for those involved’

Looking solely at mentions in Parliament, over the past few years, MPs have told of schools in their constituencies being turned down despite urgent need.

In one example last year, Robbie Moore, Conservative MP for Keighley, told Parliament that Ilkley Grammar School had a roof “prone to leaking” that had collapsed, causing “internal damage” - yet two bids to replace it had been rejected.

In another example, Harriett Baldwin, Conservative MP for West Worcestershire, said a local primary school had kept missing out despite bidding to replace its “leaky, draughty Victorian windows”.

Tim Warneford, a consultant who works on CIF applications for schools, gives further examples of rejected bids, including one for a new fire alarm safety system. Part of the unsuccessful school’s fire alarm system consisted of a handheld horn kept at reception that needed to be sounded to alert staff and pupils in another building.

He cites another example where a school boiler was 30 years old with pipework so corroded it “broke off in your hand”.

In another case, an application for funding for a kitchen at a West Midlands secondary school failed despite the kitchen being closed “due to inherent health and safety risks posed by it” (pictured below).

So why are schools like these having their bids rejected?

Ironically, it is the schools with more precarious finances that sometimes end up lower down the CIF priority list.

This is because schools need to contribute 30 per cent of the cost to score top marks in their bid. “Straightaway, some schools are capped,” says Stephen Morales, CEO of the Institute of School Business Leadership.

Not ‘a level playing field’

It is “very often the case”, Warneford adds, that the schools with less need for refurbishment but greater preparedness to invest in the financial contribution outperform the schools “with greater need but less ability to invest from their reserves”.

Indeed, of schools that have had 10 or more bids accepted since 2016, all but two are secondaries, and their average estimated revenue reserves exceeded £1 million.

Warneford says: “For those schools who are sitting on large reserves, they have the option to use them to invest in a CIF bid and accrue marks towards the threshold for an award. Trusts with deep reserves can thus secure up to six [full marks] towards the total.”

And Morales says schools that cannot access or afford technical experts, such as surveyors, are at a “significant disadvantage”, even though “their roof isn’t any less worthy of repair”.

Harnden agrees, saying that the application process is often inaccessible for schools without the help of experts.

Morales says that, even without extra funding, the government needs to at least make the system “more of a level playing field”.

“There are external people who are serially successful, but speaking broad brush, it’s likely that if you’re a very small school with limited leadership capability, you’re not going to have access to what you need,” he says.

There are other issues that experts flag up about the process.

Schools that want funding have to agree to a visit by a school resource management adviser (SRMA) as a condition, and Morales says this is difficult for some.

“The idea that you’d open up your doors to an official to assess whether you’re ‘worthy’ of the funding disadvantages certain establishments,” he says, adding: “Small schools won’t have a qualified accountant or anybody who’s qualified to NVQ level 7.”

While bigger schools will likely have an estate manager or director that can “show a robust approach to financial management”, he says, “smaller establishments don’t look as financially polished”.

Robin Bevan, headteacher at Southend High School for Boys, is scathing about the CIF marking scheme in general, calling it a “mystery marking scheme” that does not appear fully aligned to actual need.

“We’ve learned from the CIF process that it’s best to apply for projects that you can be confident will score highly, even if they’re not your top priority. It’s ultimately a form of madness,” he says.

“It’s certainly not a long-term solution or visionary commitment to high-quality learning environments for schools of the future.”

Ultimately, the complicated system has led to his school taking a more tactical approach, learning to apply for projects “that you can be confident will score highly, even if they’re not your top priority”.

Meanwhile, Di’Iasio, as well as learning more about outside experts, has treated the application process as a ”learning experience”.

He says: “We tried to learn and research who was successful, and look at who was submitting these bids well.”

He notes that schools that are not successful can also look at alternative funding sources, too.

One option for this would be urgent capital support, more details on which can be found here.

What should the DfE do?

The general consensus among experts is that to fully improve the system, there needs to be a bigger capital pot.

Bowen, for example, says that the government should fund all schools’ capital needs “properly and in full”, and “not rely on an overly complicated bidding process, which - as the data clearly shows - is failing too many schools”.

But there are other options available to the DfE.

Morales says the DfE could make the application process fairer by ensuring that schools do not have to use “very technical language in order to make the arguments” supporting their application.

“There would still be some variation across the system, of course, as some people will clearly be better at writing bits than others. But it would make sure there was less disadvantage,” he says.

Di’Iasio agrees, adding that the system should become “more transparent” around what the DfE is looking for.

As part of this, he says, a big help could come in the form of feedback that the DfE gives applicants when they are rejected.

“When we were rejected, we often found it very hard to understand why - so maybe that could be more direct,” he adds.

A DfE spokesperson says it has supported 12,400 CIF projects and allocated more than £13 billion to improve the condition of schools since 2015.

They add: “On average, around one-third of applications are successful each year, with applications solely assessed on need. We continue to support applicants throughout the application process.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article