- Home

- News

- Specialist Sector

- ‘Crisis’ as alternative provision demand surges

‘Crisis’ as alternative provision demand surges

Alternative provision (AP) is dealing with a crisis caused by rising exclusions, soaring demand for places and a growing struggle to return pupils to mainstream schools, leaders have warned.

A Tes investigation has revealed the scale of demand facing APs and pupil referral units, with many already full by last term and dealing with unprecedented waiting lists.

This is leaving pupils “stacked up like planes at Heathrow”, with APs unable to focus on preventative work that could reduce exclusions, according to school leaders.

- Background: Government’s SEND and AP plans

- Inspection: How Ofsted will investigate alternative provision

- Linked: AP providers facing a crisis

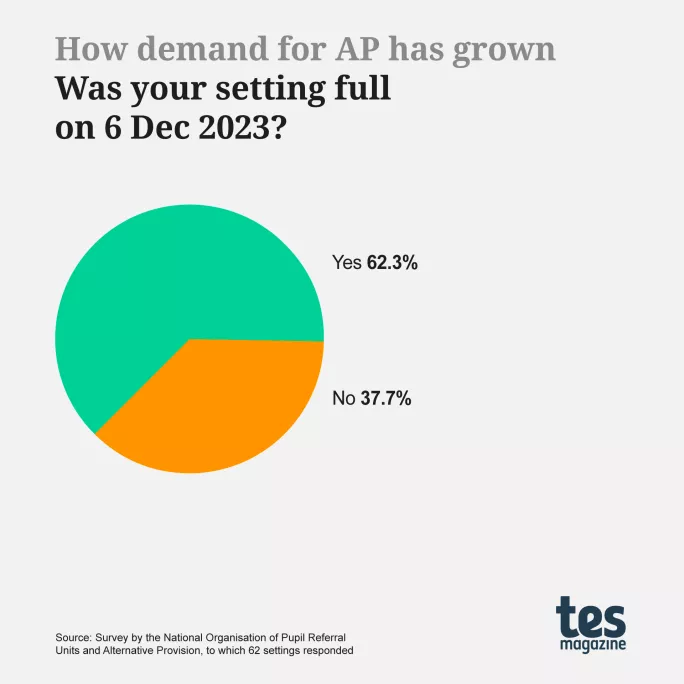

In a survey by the National Organisation of Pupil Referral Units and Alternative Provision, known as PRUsAP, more than three-fifths (62 per cent) of AP leaders said their setting was full by 6 December last year.

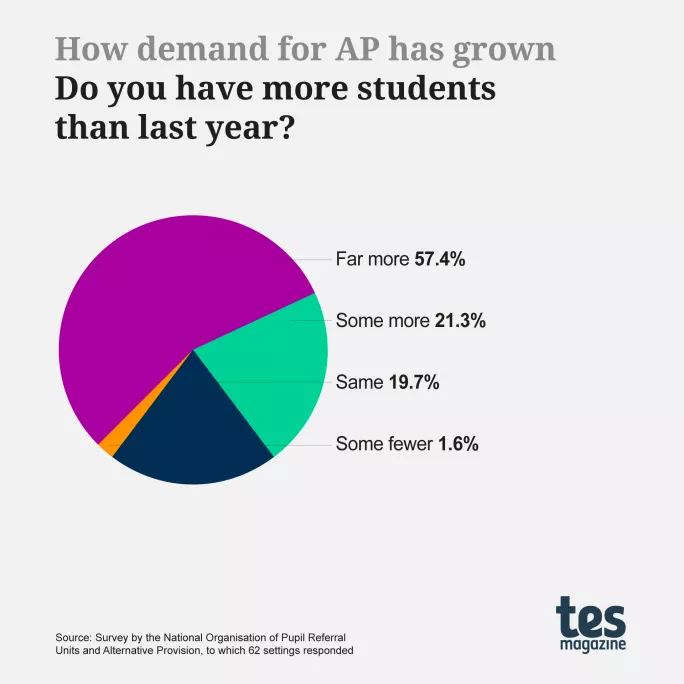

And more than three-quarters (78 per cent) of respondents had more pupils than at the same stage in previous years, with 57 per cent saying they had “far more”, according to the findings commissioned by Tes.

Just under one in five (19.7 per cent) reported a similar number of pupils to previous years.

Robert Gasson, chief executive of Wave Multi Academy Trust, which runs nine AP schools, a special school and two medical schools in Devon and Cornwall, said: “This is a crisis because APs and pupil referral units need a through-flow of pupils to work.

“Filling up earlier in the year means we don’t have the capacity to do preventative work with pupils before they become excluded. The way the system is working now means it is having to spend more money commissioning places for pupils who have been excluded rather than supporting them earlier.”

Normally, a setting that received half of its referrals from key stage 4 would expect to free up capacity as Year 11s move on each year, he explained.

“But what is happening now is these places are filled up straight away because we have a waiting list of pupils stacked up like planes at Heathrow.”

Waiting lists increasingly common

Leaders say part of the problem is that many AP pupils now have more complex needs but are unable to secure specialist provision.

At the same time, APs report having to battle to return pupils to mainstream schools, amid concerns about worsening behaviour since Covid.

All this appears to be leaving many APs short on places and having to set up waiting lists for the first time.

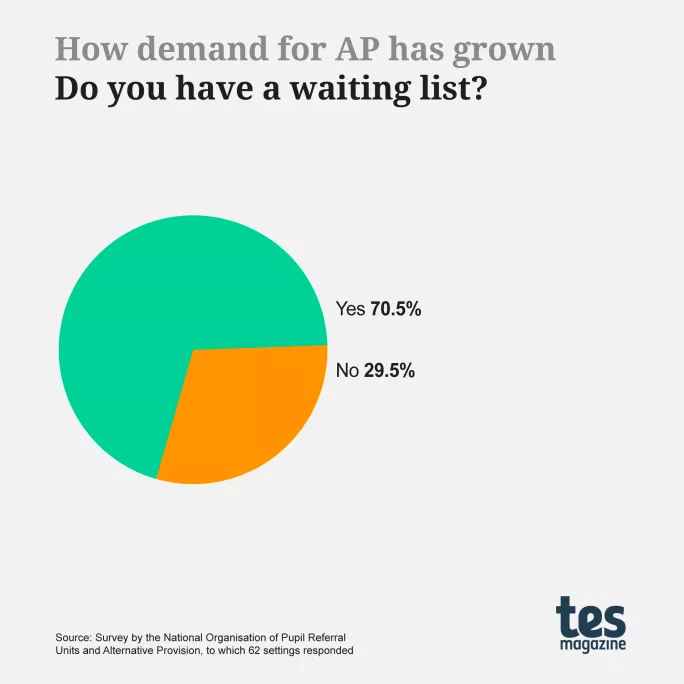

The majority (70 per cent) of the 62 units surveyed had a waiting list in place.

Of those with waiting lists, more than a third - 38 per cent - said this was the first time they had had to set one up.

The same proportion said their waiting lists had “far more” pupils than in previous years. Another 16 per cent said they had “some more”.

Meanwhile, Tes’ investigation revealed that in some areas, more than 50 pupils were waiting for a PRU place.

Of the 114 councils that responded to Tes’ request for information, 45 (39 per cent) had a waiting list. Of these, 12 said more than 25 pupils were waiting and four had more than 50 pupils waiting.

One of these was Birmingham City Council, which said that, at the time of responding, 52 pupils were awaiting a place at a PRU, who had been permanently excluded and who had all been offered interim provision.

Sarah Johnson, president of PRUsAP, said: “The situation is worrying and it’s something that, as leaders in PRU and AP, we had predicted - that demand for our sector would increase.

“Coming out of Covid, we felt more children might have mental health difficulties; children might have increasing health needs.”

The efforts of mainstream schools have been hampered by support service cuts and shortages of speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, psychiatrists and psychologists, she said.

However, there were also “some schools who will not be as inclusive as they could be or should be,” she warned.

Schools struggle with more ‘extreme’ behaviour

Steve Howell, headteacher of the City of Birmingham School PRU, agreed that a lack of access to support services in mainstream schools was leading to more referrals.

He also pointed to tightened budgets, a reliance on agency staff, and an inability to recruit or afford the support staff needed.

He said: “Inclusiveness is not about a school’s mindset. If it was just a question of mindset then I think the vast majority of schools would not be excluding. It is because of a lack of resources. I have spoken to heads who are close to tears about pupils who they are excluding.”

The rate of pupils being excluded from school in 2022-23 has returned to pre-pandemic levels, according to the latest Department for Education (DfE) statistics published in November.

Numbers rose by almost 50 per cent, to 3,104, in the autumn term of 2022-23 (a rate of 0.04), compared with 2,097 in the same period in 2021-22.

PRU and AP providers expect to see these statistics climb further when the figures for the 2023-24 autumn term are published later this year.

One of the main drivers for the trend is worsening behaviour, Mr Howell said.

He added: “It would be easy for me to be critical of mainstream schools who are excluding, but when I see some of the extreme behaviour then I understand it. I am not saying I support the exclusions but I can understand it.

“I don’t think our system is coping very well with these children.”

However, Mr Gasson said he believed that some schools’ strict approach to discipline was behind the higher number of exclusions.

“There has been an increase in the number of mainstream schools and trusts who operate a series of rules and expectations that will be difficult for some of the pupils we work with to follow,” he said, adding that this did not apply to all schools or trusts.

AP no longer a ‘revolving door’

As well as an increase in the number of pupils entering AP, there has been a slow-down in those able to return quickly to mainstream education, Mr Howell said.

“PRUs used to be thought of as having a changing cohort and a kind of revolving door, which meant as pupils leave to go back to mainstream, capacity is created. But the average length of stay for our pupils is 79 school weeks - and that is the average,” he said.

“This is not what people would expect from the model for PRUs or AP.”

This would not change any time soon because high exclusions would be “baked in for the next two or three years” owing to ongoing pressures, he predicted.

His concerns were shared widely by respondents to the PRUsAP survey, with almost all leaders highlighting problems in reintegrating children into mainstream schools.

Responses from PRU and AP leaders included:

- “Schools simply do not want our children.”

- “Schools no longer believe in our work and will not readmit pupils following an exclusion.”

- “When we’re full we have no capacity to support in-person reintegration. We’re also finding...reluctance for schools to reintegrate ‘reformed’ permanently excluded students.”

‘Impossible situation’

Julie McCulloch, director of policy at the Association of School and College Leaders, said: “The last thing that schools ever want to do is exclude a pupil and it is something that happens only as a last resort.”

The problem is that schools are under “huge financial pressures” and struggle to afford specialist support and interventions that could prevent behaviour issues “spiralling to the point of exclusion”.

She also pointed to a long-term erosion of the local support services for children and families that can play a role in tackling underlying problems with behaviour.

“In short, schools are having to pick up more of the strain of addressing a range of complex problems with less money and resources. It is an impossible situation and more needs to be done by the government to support schools in this work, and also to ensure that there is a sufficient capacity of high-quality alternative provision where this is needed,” Ms McCulloch said.

The DfE has been contacted for comment.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters