- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- How to tackle ‘micro-aggressions’ in your school

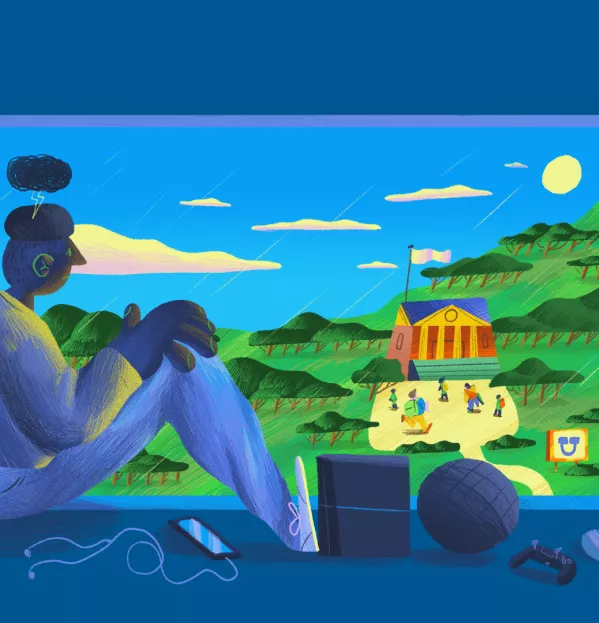

How to tackle ‘micro-aggressions’ in your school

Racism has a detrimental impact on the lives of racially minoritised young people and, when experienced, can have significant mental health consequences and, therefore, affect their ability to thrive,” says Natalie Merrett.

Merrett is the head of knowledge dissemination at the Anna Freud Centre, and for the past six months, she’s been exploring the link between racism and mental health in teenagers.

Her work has been informed by a survey that the centre conducted with 800 young people, aged between 13 and 20, from a wide range of racial backgrounds. The majority (88 per cent) said racism affects their mental health a “great deal” or “a lot”.

It’s a statistic that serves to reiterate the importance of tackling racism in the classroom and, unfortunately, the survey also revealed some worrying findings about current practice.

Here, Merrett talks to Tes about the findings, and how schools should respond.

Tes: Your research found a link between young people’s experiences of racism and poor mental health. Does that chime with other research in this area?

Merrett: Lots of literature echoes our findings. In 2019, the YMCA found that young Black people experiencing racial discrimination are likely to have low self-esteem, and high levels of anxiety and depression. They also found that 95 per cent of young Black people in the UK had heard or witnessed racist language at school.

In the past two years, it seems things have gotten worse. Research published in 2021 by EBPU, an evidence-based practice unit composed of researchers from UCL, Anna Freud and the Child Outcomes Research Consortium (CORC), found that the pandemic has had a disproportionate mental health impact in children and young people of colour.

This, of course, could be related to a range of factors, including discrimination, institutional racism, and health and economic equalities - all of which make it harder to access support.

- Why you need to know if a pupil was born preterm

- Does underlining really matter?

- Forget ‘balanced’ literacy; we need balanced learning

What did young people tell you about their experiences of racism in school?

Around 64 per cent of young people we surveyed said they had discussed racism with staff in their school or college, but just 26 per cent said that teachers and tutors understood the impact that racism has on mental health.

Students raised issues ranging from unconscious bias and understanding the impact of racism on mental health, to racist language and micro-aggressions.

One young person said “racist behaviour is seen as normal”, and the majority said schools needed to [do more to] “call out racism” when it happens.

Young people also said there is a lack of understanding of what is considered racist, and want teachers to undergo training. In particular, education staff need to understand the scope and impact of micro-aggressions, and the impact the behaviour has on students.

What is a ‘micro-aggression’?

This is when a person makes a passing remark or does something small to discriminate against members of a minority group, either deliberately or by mistake. It is a subtle or indirect form of racism.

In school, teachers might perform micro-aggressions themselves without realising. Examples include mispronouncing the names of students, even after being corrected, scheduling assessments on major holidays for religions other than Christianity, or asking a student to speak for, or to represent, their entire ethnic group.

It’s important that teachers are aware of the impact of this behaviour. We cite a systematic review into micro-aggressions published in 2021, which found racial micro-aggressions are linked to low self-esteem, increased stress levels, anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts.

All of those feelings can then lead to children disengaging and, eventually, dropping out of education.

If micro-aggressions can happen by accident and go unnoticed, how can teachers keep them out of their classrooms?

Teachers need to reflect on their own attitudes, stereotypes and expectations. When talking about a particular group of people in a lesson, it’s good practice to assume that the group is always represented in the classroom. You should avoid singling out students, or asking students to speak for the experience of an entire group of people.

Teachers are also likely to witness micro-aggressions between students. When this happens, the behaviour or attitude needs to be challenged, rather than the student themselves, and teachers should emphasise that the impact of what was said is more important than the intent behind it. Ask students to rephrase or rethink comments and, where possible, challenge stereotypes with accurate information in the moment.

Crucially, if a student wants to discuss a micro-aggression, don’t say things like, “I’m sure they didn’t mean anything by it”, but instead, listen to and validate those feelings.

Not every act of racism would be considered a “micro-aggression”. What should teachers do about more direct racism?

Be conscious that just because students haven’t reported racist incidents, it doesn’t mean they aren’t happening. It’s important to create a safe space for students in which they can disclose information with the confidence that action will be taken.

Every single member of staff needs to actively challenge attitudes and behaviour: for classroom teachers, you could create a class contract or guidelines for everyone to follow.

When an incident does happen, holding a “debrief session” post-lesson can be really helpful.

How can schools improve their culture to help minimise racist incidents and safeguard mental health?

In our survey, students identified key areas of improvement, and we have used those to create a five-step approach that we believe every school should adopt.

As a starting point, schools need to acknowledge and address racism when it happens. Leaders should review school policies to ensure they are equitable, set up a working group to diversify the curriculum and ensure it’s representative of the student population. Any plans need to be clearly communicated to staff, parents and students.

The second step is around recognising the value of working in partnership with staff, students and parents, as well as organisations and stakeholders in the community. Leaders should consider how to put on cultural exchange activities in a sensitive way.

Crucially, student voices must be encouraged: schools need to understand the issues students are facing, and how they want to be supported. This could be done through anonymous surveys.

Should schools be explicitly addressing issues around mental health alongside this?

Yes. It’s incredibly important that schools assess and meet the mental health needs of students, identify those at risk, and develop interventions: this is step three of the approach.

The anonymous surveys can help with this, but you need to be clear about the reasons you’re doing it and how that information will be used.

Mental health and wellbeing also need to be integrated across the whole school curriculum: this is step four of the plan.

For example, student wellbeing is boosted when they see their ethnicities represented in the school curriculum: setting up an anti-racist curriculum working group can ensure that work is happening right across the school to diversify the curriculum, and not just in individual lessons.

At the same time, leaders also need to think about their staff. This is the final step of the plan: senior leaders should look closely at staff demographics and think about ways in which they can improve hiring practices to be more diverse.

Supporting the wellbeing of all staff should be a priority and, once again, anonymous surveys are a good way to find out about the needs of staff from all backgrounds.

How can schools implement all of the above when they are so stretched for time and resources?

Lean on the people around you. There are lots of great schools that are actively involved in anti-racism work and which can support others. You don’t have to do this alone.

There are also lots of community groups in areas across the country that are willing to come in and do workshops and work with schools for free. The Runnymede Trust, NEU Black Educators and NAHT Leaders for Race Equality are all great examples.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article