- Home

- ‘Getting PGCE students and NQTs to mark A level and GCSE exams? The money might not be good enough...’

‘Getting PGCE students and NQTs to mark A level and GCSE exams? The money might not be good enough...’

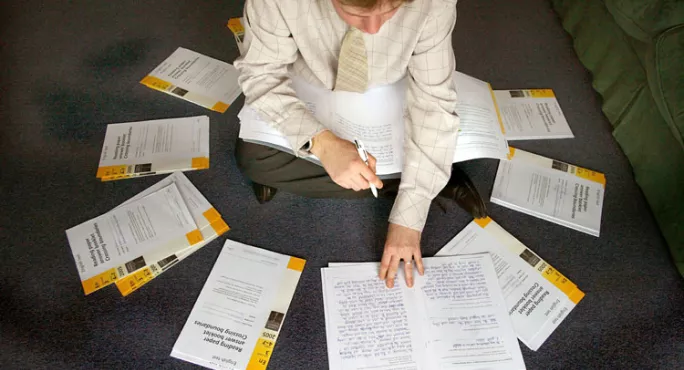

At this time of year, leaflets from exam boards asking subject leaders to encourage their staff to examine are nothing new. There has always been a shortage of examiners.

What is new is that this year the newest members of the profession - and some outsiders, such as PhD students - are also being targeted.

The string of comments under the Tes article ”Exam boards ask students and NQTs to mark GCSE and A-level exam papers” earlier this month shows that I was not the only one initially horrified by this news.

It sends a signal that overworked teachers are not volunteering: even OCR’s cruise-ship initiative to sign up retired teachers on holiday and bus-stop advertising are floundering.

In an ever-more-severe accountability system, we might be concerned at the prospect of students’ results being in the hands of the least experienced - not to mention the impact on the data that drives performance-management and school inspection judgements.

Moreover, the subjects at risk are the most subjective, such as English and history, those with the highest wastage rates of examiners, according to Ofqual’s studies in 2014, and those that generate most appeals. The risks appear to be higher than ever before as reformed qualifications come to fruition.

There is some fairly dated research by AQA suggesting that PGCE students and NQTs can make assessments, in some cases, as accurately as experienced examiners - but only in GCSE English. This might be used to justify relaxing recruitment criteria, but has anyone researched the impact of larger numbers of less experienced teachers in live sessions?

Would A levels be a bridge too far?

Ofqual’s symposium showed that the higher the mark per essay, the greater the problem in achieving consensus across examiners. The less experienced teachers would have great difficulty in differentiating between essays which vary so widely in content and approach.

The case against the PGCE and NQT examiners seems almost overwhelming in this crucial year.

The positives

The argument against PGCE and NQTs overlooks the potential value of professional development and long-term engagement with the examination system from the start of a teacher’s career.

Currently, understanding of external standards is left in the hands of teacher-training bodies and school departments, where some suspicions of secret knowledge abound, especially where academy chain bosses refuse to release teachers.

Serving as examiners would make new teachers more independent and autonomous. Armed with knowledge, they could play a significant role in their institutions.

A generic professional programme

The drawback, of course, is that in subjective disciplines A-level specifications differ so widely across different awarding bodies, and in English across the three separate strands. “The knowledge” would be rather compartmentalised.

What new teachers - and the profession as a whole - need is a more universal and generic programme embedded from early training to address Standard 6 (accurate assessment of pupils’ work).

This should take the form of an introductory unit on the principles of assessment, followed by sessions on each specification at GCSE and A level, some trial marking and evaluation of suitability to mark.

From the supply side, this would give exam boards information about potential recruits. It would be a step in the right direction of professionalising examination marking.

Who should pay?

Since this would be in the long-term interests of exam boards, it would not be unfair to expect from them a substantial input in the form of trainers and some funding to support national generic training. For the boards, the benefits of engaging with new teachers are obvious.

Those of us who were there at the inception of GCSE remember the training, which was very powerful in cementing our loyalties to individual boards long into the future.

As major beneficiaries, trusts, individual centres and LAs could contribute on a pro-rata basis, depending on the number of delegates. They could then expect teachers to make better predictions and assessments to feed the accountability data, and to provide better information to parents, inspectors and senior managers. The effect on their teaching could be quite powerful as well.

Arrangements for this year

However, what is needed urgently in the short term is excellent initial training prior to the standardisation days at the start of the marking process.

Is online standardisation really sufficiently robust when the examining professional cohort is so much more diverse and potentially less experienced in the classroom? Its benefits in terms of speed and cost should be weighed against the deeper learning required to sustain the standard to the end of the marking period.

Stronger supervision for all examiners and closer contact between team leaders and teams are called for, especially if boards are strongly wedded to remote standardisation. This mentoring would be invaluable for new recruits learning a lot not just about the examining process but also teaching strategies.

Face-to-face training - where scripts can be discussed and early misunderstandings ironed out - would surely be the best option. Even with examiners working against the clock, speed of standardisation is not the only important factor.

Costs and benefits

Finally, what any skilled professional examiner needs, of course, is a database of exam boards’ fees and any bonus arrangements. Is participation in the initial standardisation paid for up-front or subsumed into the fees? Then the costs of ICT requirements are needed to gauge start-up costs and evaluate the competitiveness of benefits packages.

Unfortunately, for all our fears of an influx of PGCE and NQTs, the sad truth may well be that they can earn more money less intensively elsewhere.

Yvonne Williams is a head of English in the south of England. The views expressed here are her own

For all the latest news and views on the exams, visit our specialised GCSE and A level hubs.

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters