- Home

- Teaching & Learning

- General

- Why one-size-fits-all behaviour policies don’t fit all

Why one-size-fits-all behaviour policies don’t fit all

I wonder if any of you are still teaching in science labs like the one I started my teaching life in?

Pairs of hexagonal tables fixed to the floor with central islands between the hexagons for water, gas and electricity. Great for storage of practical equipment underneath (no legroom for the teenagers, mind), but problematic in many other ways because the tables were immoveable. And because the students faced six different ways (always facing someone else), but rarely towards me.

I used this excuse for two years to explain the fact that I could never tell the difference between Amy and Natalie Griffiths.

I was reminded of this lab of mine when I heard the secretary of state for education’s recent proclamation that ”traditional teacher-led lessons with children seated facing the expert at the front” were “powerful tools for enabling a structured learning environment”.

Well, OK. Presented with a standard box room, my preference - along with that of many others - is for my class to be seated in rows. I have taught maths recently under just such an arrangement.

Behaviour: The unofficial pecking order of teaching children

But whenever I hear this facile advice, a number of things pop into my head. I think of my colleagues teaching in sports halls, and on fields and pitches, in drama studios, workshops, computer suites, studios. I think of my early years colleagues, with their seamless provision between the indoor and outdoor learning environments. I think of my colleagues in special schools, working with children with profound and multiple learning difficulties.

I keep returning to the word “structured”. Maybe I’m reading too much into it, but its inclusion suggests to me that an absence of rows is an indicator to Gavin Williamson of a lack of structure. Which is, of course, ridiculous.

I have a strong suspicion that Mr Williamson has an image in his mind of a class of teenagers in one of those standard classrooms studying what he might regard as a traditional academic subject, like English, maths, a language or history. Proper teaching: rigorous and academic.

This fits with what I have long suspected is in some minds the unofficial pecking order of teaching children: secondary specialist subject teaching is regarded as proper teaching; the primary jacks of all trades come next, followed behind by early years and special-school teachers (“It’s almost like a normal school,” a visiting colleague said to me once).

The nature of the task should dictate classroom seating

To be fair to the secretary of state, he is not the first, and won’t be the last, to offer up this pedagogical gem about how our students should be seated. But every time it does come up, you could do worse than reflect on Wannarka and Ruhl’s paper from 2008, Seating arrangements that promote positive academic and behavioural outcomes: a review of empirical research.

They emphasise that: “Evidence supports the idea that students display higher levels of appropriate behaviour during individual tasks [my emphasis] when they are seated in rows, with disruptive students benefiting the most.”

So far, so Williamson, and no real surprise to us given that it plainly makes inappropriate interactions between classmates more inconvenient (compared with my hexagons of hell), and we are more likely to spot them, too.

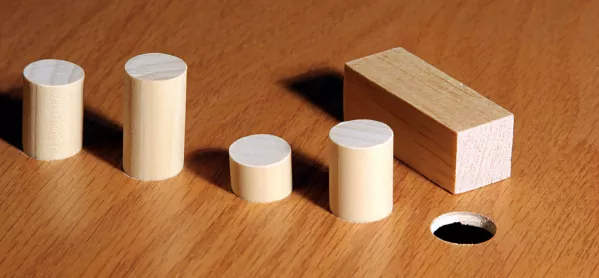

However, the authors conclude in a statement so stunningly obvious that anyone surprised by it should be barred from holding ministerial office: “There is no single classroom seating arrangement that promotes positive behavioural and academic outcomes for all tasks, because the available research clearly indicates that the nature of the task should dictate the arrangement.”

And that, of course, is not the end of it. More important, in my view, is your decision on who sits where. Wannarka and Ruhl cite research suggesting that a student’s location in the classroom is related to the number of questions received from the teacher, and that students at the back of the classroom tend to interact with each other more frequently than those seated at the front, potentially adversely impacting their attention to the task at hand. Two of the many reasons why we almost always use seating plans.

I am grateful to the secretary of state for his contribution to the discussion, but I will continue to back my colleagues to set out their classrooms and decide who sits where to best support behaviour, attention, peer relationships and learning.

Jarlath O’Brien is the author of Better Behaviour - A Guide for Teachers, and works with children with social, emotional and mental health needs

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article