How England lost its teachers - and how it can get them back

England is slowly running out of teachers.

Since 2010, the supply of new trainee teachers compared with need has slowed to a trickle while the rate at which teachers are leaving the profession has continued to grow, leaving schools stuck in a vicious cycle of low recruitment and high attrition.

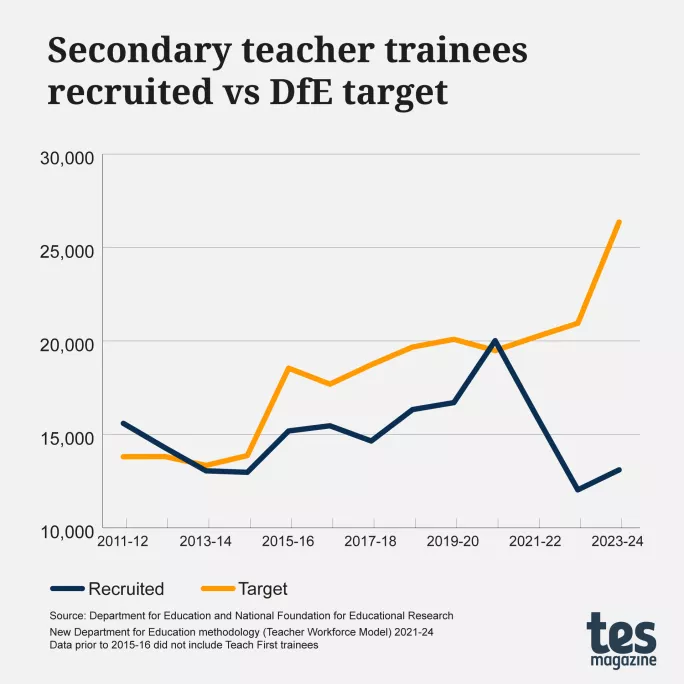

This year, the government missed its recruitment target for secondary teacher trainees by half - continuing a broader trend of missed targets.

And while the picture at primary is, on the surface, better - the Department for Education recruited 96 per cent of the primary teacher trainees it needed to reach its target this year amid falling pupil rolls - it is worth noting that recruitment fell by 17 per cent year-on-year in 2023, leaving experts concerned.

In the specialist sector, there is not an assigned DfE target - teachers generally move to special schools after training on a primary or secondary course - but special schools do have the highest rate of temporarily filled or vacant posts, says Simon Knight, joint headteacher at Frank Wise School in Oxfordshire.

Warren Carratt, CEO at Nexus Trust, which has 14 special schools, says “there is an acute pressure” in recruitment and retention in special schools “that the government just doesn’t seem to recognise”.

A rise in initial teacher training (ITT) recruitment during the Covid-19 pandemic proved only a temporary reprieve for the system: the trend in the years following has again been downward.

Meanwhile, the number of state school teachers leaving the profession hit its highest rate in four years in the academic year 2021-22, with one in 10 (43,997) recorded as quitting the classroom.

A ‘dire’ situation

In the years before the pandemic, the leaving rate rose to around 10.6 per cent but then began to fall slightly. In 2018-19, the last pre-pandemic year, it was 9.4 per cent.

Now, experts are concerned that the wash of increasing pressures facing schools will drive that stat higher, and the Commission on Teacher Retention warned this year that “getting workload under control once and for all has perhaps never been more critical than now”.

Reasons for optimism are hard to find.

Jack Worth, school workforce lead at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), has described the situation for recruitment and retention as “dire” and says it proves the need for “urgent and radical action”.

So, can the workforce crisis be fixed - and, if so, how? To be able to answer that, you first have to know what is broken and why.

The role of teacher pay

The most obvious place to start - because it has been the most high-profile issue cited by unions in teacher supply - is pay.

Sam Freedman, senior fellow at the Institute for Government and a former DfE senior policy adviser, feels strongly that teacher recruitment is very closely linked to pay rates in the wider economy.

He says that the government made a decision to “restrain public sector wages” in order to manage “very difficult public finances”.

“It has caused very serious recruitment problems for the public sector across the board,” Freedman claims.

‘There is no way around the fact that this is a question of money’

A recent report by the Nuffield Trust warned that the NHS was “understaffed and under strain” owing to the domestic training pipeline for clinical careers being “unfit for purpose”.

It stated that around one in five radiographers, nurses, occupational therapists and physiotherapists have left NHS hospital and community settings within two years.

And a 2022 report by the Health and Social Care Committee warned that the NHS and the social care sector were facing “the greatest workforce crisis in their history”.

Freedman thinks that there is “no one else to blame but the government” for the non-competitive wages - and, therefore, recruitment and retention problems - in the public sector.

Is a ‘full correction’ to pay forthcoming?

That stagnation of teacher pay has affected recruitment and retention, in particular, is something that the experts agree on.

Earlier this year, a report by the NFER suggested that “teacher pay has grown more slowly than average earnings in the wider economy”.

The NFER suggested that a “full correction” to teacher pay would mean a rise of 16.5 per cent in 2024-25 for all pay points, with a return to 2 per cent per year from 2025-26 onwards.

The government has given no indication that such a rise to teacher pay would be feasible or considered. However, there is no doubt that the DfE is using other financial incentives to tempt graduates into teaching.

For example, it has managed to keep to the Conservative manifesto commitment of giving teachers a minimum starting salary of £30,000.

But, as Worth has noted, the landscape has “really changed” since the new starting salary was announced as an ambition, with “average earnings increasing by more than we expected them to in 2019” - which has had a knock-on effect on how competitive that £30,000 now is.

The government has also introduced levelling-up payments for eligible teachers in schools identified as having a high need for supply.

Reintroduction of ITT bursaries

Another use of financial incentives on the recruitment side has been bursaries. The NFER has estimated that a £10,000 increase in a subject bursary is associated with an 18 per cent increase in the number of trainees in that subject, though this can vary depending on the cohort.

For the 2023-24 cohort, the DfE increased maths, physics, chemistry and computing bursaries to £27,000, while bursaries for languages, ancient languages and geography increased to £25,000.

The biology and design and technology bursaries rose to £20,000, and a £15,000 bursary was reintroduced for English.

For 2024-25, the bursaries in some subjects have been raised even higher.

As the NFER found, this had a positive impact but is merely a “sticking plaster solution”. It tackles the “symptoms of the crisis” rather than the cause, sector leaders have said.

Funded routes into teaching

Furthermore, ITT providers report a clear difference in the ability of trainees without a bursary to afford to train to teach.

Indeed, James Noble-Rogers, executive director of the Universities’ Council for the Education of Teachers, says the government needs to look at ways of supporting students on programmes, such as establishing a universal hardship fund or more retention incentives.

And John Camp, president of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), wants to see expanded salaried and fully funded routes into teaching, as well as adequate funding at the training level, “to enable people to do their year’s training without their financial situation being unduly compromised”.

Freedman also calls for the scrapping of the postgraduate certificate in education fee in order to tempt more into teaching - and get rid of that “disincentive”. But he says the government won’t do that because they don’t want to set that precedent for tuition fees.

What about financial incentives for those teachers already in the system? Generally, experts feel that teachers are more receptive to financial incentives at the beginning of their careers. However, pay awards are still important, as the earlier pay stagnation research made clear.

‘The next government is really going to have to crack how teachers get the right to work flexibly’

Geoff Barton, general secretary of ASCL, says it was “very important that decent uplifts are applied to all salary points on the teacher and leadership pay scales” to help “reduce the current attrition rate”.

And Paul Whiteman, general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union, says that the pay of experienced teachers and leaders “has fallen by about a fifth in real terms since 2010 against inflation”.

“The government needs to address the pay levels of experienced teachers and leaders, and their pay progression, if it wants to improve retention, and encourage teaching professionals to commit to develop their careers and move into leadership roles,” Whiteman adds.

But, as anyone in the sector will tell you, money isn’t everything.

Have DfE initiatives harmed recruitment?

At the ITT end of the market, some in the sector feel the government policy initiatives around structure have actually harmed recruitment rather than improve it.

The recent shake-up of the teacher training market, in which the DfE oversaw the rollout of a reaccreditation process for providers, has been described by some providers and others in the sector as disastrous and destructive, and even elicited concerns from some who worked on the project.

Many in the sector were concerned that the process could leave many areas of the country without training provision amid a supply crisis.

The worst fears of the sector have yet to come to fruition, however, with many of those who failed accreditation forming partnerships with other providers to ensure enough places in the right areas are still available.

The population ‘bulge’

As training providers warn of shortfalls, former DfE adviser David Thomas argues that one problem is that there are just more pupils to cater for. He explains that one of the major challenges around recruitment has come with the population “bulge” that is moving out of primary schools and into secondaries.

Essentially, we now have to recruit more teachers at secondary level than before to meet demand.

Freedman argues that the population bulge cannot be used as an excuse as “we knew it was coming” and “managed it fine for primary”. However, he concedes that “secondary is always harder to recruit for than primary”.

He thinks things will become easier over the next decade as pupil numbers drop, but “probably not by enough to solve the problem, sadly”.

The government’s ‘golden thread’

If recruitment into the profession is tough then keeping teachers in it seems even harder.

Data released by the DfE earlier this year shows an increase in the number of new teachers leaving the sector after one year - from 12.4 per cent in 2020 to 12.8 per cent in 2021. And, as mentioned above, 43,997 teachers left the state-funded sector in the academic year 2021-22.

In recent years, the department has developed its “golden thread” of teacher development - reforming teacher training and professional development, as well as introducing the Early Career Framework (ECF) - in a bid to make the teacher experience better and, ultimately, help them stay longer.

The launch of the ECF introduced a two-year programme of structured training and support for early career teachers. However, since its launch in 2021, the framework has attracted concerns over workload and lack of flexibility.

The government is currently carrying out a review of the framework to address some of the concerns.

Has the ECF made a difference?

However, research by the Gatsby Foundation and Teacher Tapp, published in May, looked at the ECF one year in and found that almost eight in 10 mentors (78 per cent) believed early career teacher support would neither increase nor decrease the retention of ECTs.

In reality, though, the question of the effectiveness of the ECF still hangs in the balance as the sector waits for definitive long-term data on its impact.

Freedman says that the 2023 retention figures will be important to determine how retention post-Covid compares with pre-pandemic levels.

And this is when the first picture of the impact of the ECF could begin to emerge. However, others have pointed out that it will be difficult to determine what is and is not the impact of the ECF.

Despite this, many working with the sector and advising the government want the reforms to go further.

Looking to the future, Sam Twiselton, emeritus professor at Sheffield Hallam University and government adviser, says that she would like to see the big premium that’s been put on mentoring and coaching in the ECF and ITT “continue as an entitlement for everybody”.

But she adds that money will be the deal maker or breaker here as more teachers are needed in the system to make that effective and not a workload burden.

Indeed, workload is already the major factor in teachers deciding to leave the profession.

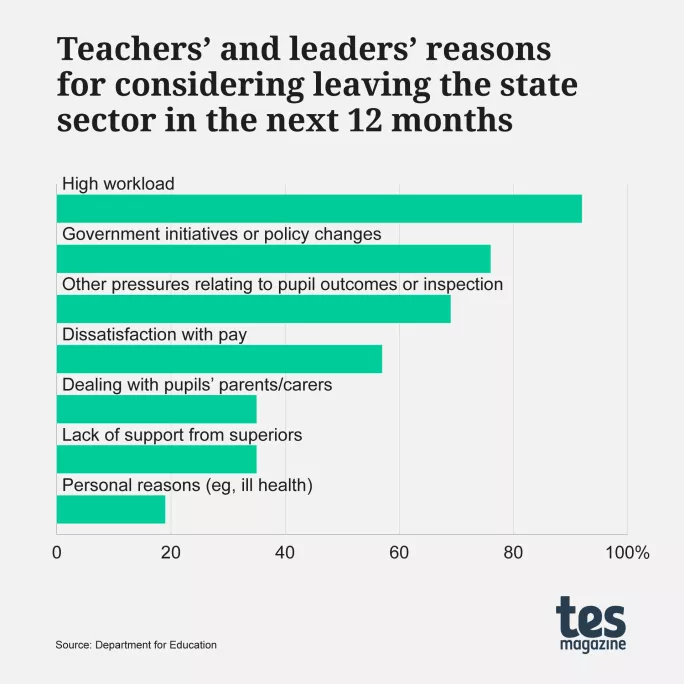

The DfE’s Working lives of teachers and leaders survey, published in April but reporting findings from 2022, revealed that 26 per cent of teachers and 21 per cent of leaders said they were considering leaving the state sector (excluding retirement) in the next 12 months.

When asked to rate the most important factor in that decision, teachers and leaders most commonly reported high workload as an important factor, with 92 per cent of respondents mentioning it.

The next most commonly selected reasons were government initiatives or policy changes (76 per cent) and pressures related to pupil outcomes or inspection (69 per cent).

The government has certainly placed a strong emphasis on workload reduction. Since 2010, the Conservatives have sought to clarify the expectations of Ofsted in order to reduce what they deem to be unnecessary work.

The DfE also claims to have overseen the removal and simplification of a number of duties, guidance, data collection and bureaucratic tasks affecting schools.

In 2015, the government announced the introduction of a minimum lead-in time for significant accountability, curriculum and qualifications changes, and said it would not make changes to qualifications during a course.

An Ofsted commitment was also introduced to ensure the inspectorate did not make substantive changes to the school inspection handbook or framework during the academic year.

In addition, the department committed to biannual workload surveys to track trends and sought to reduce marking time for teachers and tackle “deep marking”, as well as produce guidelines for data collection in schools to reduce workload.

Teacher workload reduction efforts

Then, in 2022, the government relaunched Oak National Academy as an arm’s-length body with an aim to reduce workload by encouraging the use of ready-made curriculum resources. In recent months, Oak has been trialling artificial intelligence tools to help reduce workload.

And finally, the DfE has set up the workload reduction task force with the aim of reducing teacher workload by five hours a week.

But have any of these efforts made any discernible difference?

Thomas says that while the government had seen a “shift in schools” to make teachers’ lives easier and reduce working hours, a “bunch of it has been undone” by the pandemic.

Michael Tidd, headteacher at East Preston Junior School in West Sussex, says that previous government initiatives “did have an impact and some of those old issues are less common” - for example, he believes new directions on marking have made a difference - but “plenty of other things have filled the void”.

Though he says Covid recovery is partly to blame for undoing some of the progress made on workload, he insists that there are other factors at play.

For example, he cites an increasing number of families “struggling simply with survival” and “the growing crisis in virtually every other service since austerity”.

Schools filling the gap in social services

The existence of workload that is not directly in the power of the DfE to tackle is also raised by Glyn Potts, headteacher at Newman RC College in Oldham.

Potts says that, since Covid, “the complexities faced by students, the level of need and the erosion of services from external partners have led teachers to feel morally obligated to fill the gap”.

He adds that in schools in areas of deprivation, “this is like running with your shoes tied…Clear data on recruitment and retention points to a clear outcome”.

In a recent study conducted by the NFER and published by the Education Endowment Foundation, Worth stated that many teachers are stressing the importance of “external drivers of workload”.

And Sinéad Mc Brearty, chief executive officer of charity Education Support, adds that whoever wins the next election will have to invest in the services that people should be going to, such as the “unmet need in Camhs”, or ”[putting] a lot more adults and resources into schools because that’s where people are going for support”.

Asked if a collapse of these support services and the resulting impact on schools is the fault of the government, Freedman says that is his “biggest criticism of government policy in education”.

‘The profession is trapped in a negative discourse about teaching’

He thinks that this factor has had a significant effect on retention, in particular the retention of more senior teachers.

And Thomas concedes that it is “clearly the case that schools are feeling a lot of pressure and something is going on with young people’s mental health across the English-speaking world”.

The figures are clear on that point: the latest wave of the Mental Health of Children and Young People in England NHS report found that one in five children and young people in England aged 8-25 had a probable mental disorder in 2023.

But, Thomas says, “there isn’t a country that has got an approach to that nailed” and says we need a plan to tackle this challenge.

Mc Brearty says there is “no way around the fact that this is a question of money” and that “there needs to be a substantial settlement with the education sector”, otherwise “the cost down the road will be enormous”.

Lack of flexible working

Away from workload, another key factor putting people off going into teaching and staying has been a lack of flexible working.

Asked if increased flexible working in sectors outside teaching is making recruitment and retention in the schools sector harder, Thomas answers “definitely”.

He adds: “Most jobs that people would consider as similar to teaching can all now work from home as a norm.

“This makes them relatively more appealing and so the contrast makes it harder for teaching to stay attractive.”

The DfE has produced toolkits and case studies to help schools adopt flexible working practice, as well as introducing regional flexible working ambassador multi-academy trusts and schools.

But a recent poll of senior leaders by Teacher Tapp revealed that just 4 per cent of leaders found the flexible working toolkit useful. And many still see teaching as a relatively inflexible profession.

Mary Bousted, former joint general secretary of the NEU teaching union, thinks that the next government is “really going to have to crack how teachers get the right to work flexibly”.

Teachers are ‘frontline workers’

But Worth argues that something that will need looking at in the long run is “how the teaching profession responds to the fact that teachers are essentially frontline workers” and don’t have the opportunity for a huge amount of flexibility, or the ability to work from home, like lots of graduates.

He adds that it’s important for any government to look at how the teaching profession goes about compensating for that change.

“We need to look at other things like how we compensate through, for example, pay for keeping teaching competitive with other professions that do now have more flexibility,” Worth adds.

Pressure of Ofsted on heads

Yet another area affecting retention is accountability. Well-publicised league tables, performance measures and single-word Ofsted judgements have all added up to a storm of discontent and, in some instances, unmanageable stress.

Dave McPartlin, headteacher of Flakefleet Primary School in Fleetwood, says that school staff “resent being in the window” waiting for Ofsted. He says the “pressure just ramps up until you eventually get the call”.

McPartlin explains that he hears from a lot of heads who are retiring early because they don’t want to go through another Ofsted inspection, adding that it takes a toll on your mind.

He says he has “quite often ended up on antidepressants” and it takes a toll on retention, too.

Vic Goddard, co-principal of Passmores Academy in Harlow, says inspection can mean people lose their jobs and “damage the mental health of public servants that are simply striving to help their communities”.

Freedman thinks that having an inspectorate is important, but that inspection is clearly an issue when it comes to the retention of school leaders.

Is teaching a rewarding career?

Finally, on top of all this, there is an argument happening about the perception of teaching. A government source tells Tes that “the unions should advocate for their profession. They could make a big difference by talking more about how rewarding a career as a teacher is”.

Some in the profession agree that the narrative put out by the sector is that this is not a place anyone would want to work. While there are challenges, there is a huge amount to celebrate, too, and that should have equal billing, they claim.

Ormiston Academies Trust CEO Tom Rees, who runs more than 40 schools across the country, says the sector “needs to be prepared for it to be challenging for a long period of time”.

Rees says that the profession is “trapped” in a “negative discourse about teaching”.

While he argues that some of this is “inevitable because of industrial action”, he also says “some of it comes because important arguments are being made to invest in teaching, and so the consequences of underinvestment have to be explained”.

Unions ‘speak the truth’

But responding to the government source, Bousted says “government sources always say that” and they are telling the profession to “deny the evidence of our senses”.

“This seems to be a government that thinks that it can say that everything’s fine in the teaching profession when it’s clearly not fine,” she adds.

Bousted says that the government should not “castigate” the unions for “speaking the truth about the huge scale of problems in the profession”.

And she adds that the government was doing a “very good job” of talking the profession down all on its own.

Doing nothing is not an option

Added together, it is pretty clear why we have a recruitment and retention crisis in teaching. But what is also clear is that there are at least solutions available.

The list of challenges for whoever wins the next election is long and there are no easy options; fixing recruitment and retention will not only cost a lot of money but also take a considerable amount of time.

But doing nothing is not an option.

The crisis is with us right now and the danger of a spiral into deeper trouble is very real. With every passing month that radical action does not occur, the problems will get even tougher to tackle.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article