Will teachers ever have flexible working?

How flexible is your job? By that, I mean: can you pick and choose your own hours? Can you have every Tuesday afternoon off to care for a loved one? Can you book off a Friday to go to a wedding with ease?

Traditionally, if you’re a teacher, the answer to these questions is “no”.

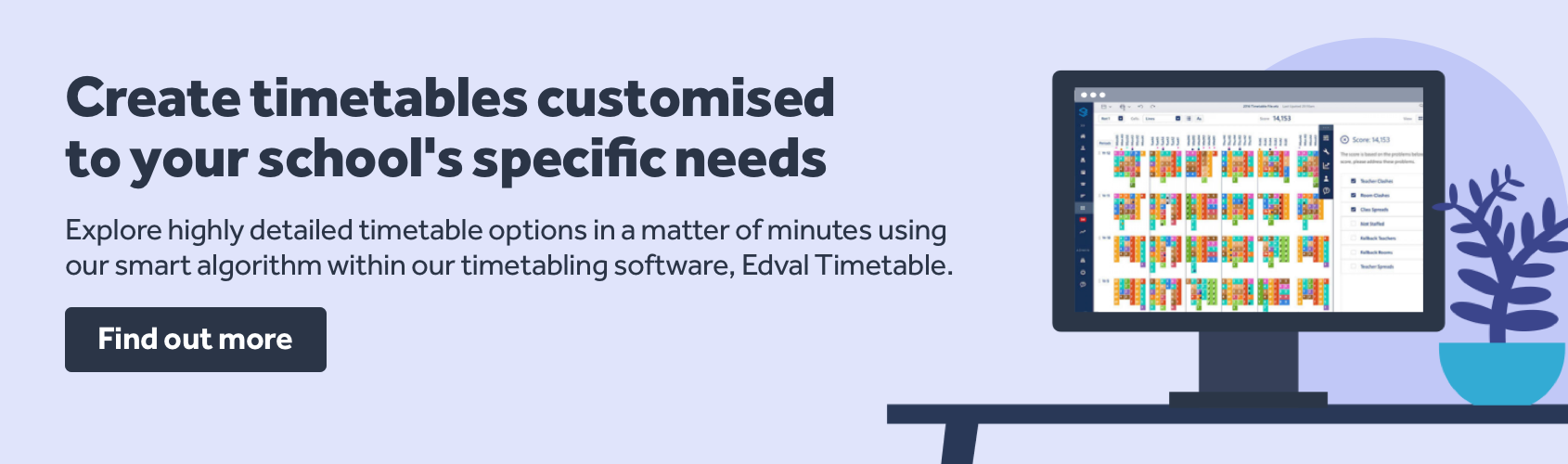

To anyone who has spent time working in a school, the reasons for this will be obvious. A report published in 2019 by flexible working consultancy Timewise sets them out in black and white. The report identifies three categories of barriers that teachers face when it comes to flexible working. The first of these is structural: timetabling, student-staff ratios and cover all come under this umbrella, as do budget, workload and the intensity of the school day.

In other words, teachers are a slave to the timetable, says Charlotte Gascoigne, a principal research fellow at the school of management at Cranfield University, and author of the report.

“Teaching is really quite constrained compared with many other jobs. You have some flexibility at the start and end of the day but, for people who are working full time, it is really quite hard to get time flexibility because of the timetable,” she says.

“You have to be standing in front of the class at the point when the timetable tells you to be, and that does limit the time flexibility in comparison with corporate jobs.”

The second set of barriers is all about culture and attitude: a fear from leaders that once you offer flexible working to one teacher, everyone else will want it; concerns about unfairness; differing opinions about the validity of reasons; worry about the impact on students; a fear that flexible working hinders progression; and management capacity.

The third set of barriers is down to a lack of expertise in education. Because teaching hasn’t traditionally been a flexible profession, leaders don’t have the skills to redesign jobs.

The challenges for schools in providing flexible working for teachers

In the past, teachers might have been willing to accept these barriers. But times have changed. We now know that teaching does not have to take place in person, in the classroom - at least, not all the time. And other sectors are already demonstrating the extent to which once rigorously enforced working practices can shift.

Earlier this year, a report by the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) found that 63 per cent of employers planned to introduce or expand the use of hybrid working to some degree post-pandemic.

“Perceived barriers in the ‘nature’ of the work - which were said to render remote working impossible - have faded away as managers have learned to design work differently,” the report states.

Add to this the fact that the pandemic has made many people reassess their priorities and existing work-life balance, and it would be no surprise if teachers were no longer content to be slaves to the timetable.

The question is: is education willing, or able, to adapt?

A clear case

Emma Turner, research-informed continuing professional development lead at the Discovery Trust, argues that the sector doesn’t have much choice but to react.

“The profession is crying out for flexible working,” she says. “We’re just haemorrhaging teaching talent - and not only [that] but we’re precluding people from developing within the profession because they can’t take the next step or take on a particular role because those roles don’t traditionally offer flexibility.”

The research backs Turner up: teaching is certainly haemorrhaging talent. According to a briefing note on the House of Commons, since 2011, the overall number of teachers has not kept pace with increasing pupil numbers, with teacher-to-pupil ratios becoming more unbalanced. The number of full-time teacher vacancies and temporarily filled posts have risen over this period, too.

And while there has been an increase in initial teacher trainees (in 2020-21, overall recruitment was 15 per cent above target), researchers say it won’t reverse the shortages that have built up over several years (see pages 14-15).

Is a lack of flexible working the only cause of this continuing problem? Clearly not. But, as Turner suggested, it is having a much bigger impact than you might expect, as demonstrated by recent evidence.

For example, a National Foundation for Educational Research report, published in 2017, found that greater flexibility over working patterns may encourage teachers to stay in, or return to, the profession.

The report’s authors - Jack Worth, Jude Hillary and Giulia De Lazzari - encouraged the government and stakeholders in the secondary sector to urgently look at ways of accommodating more part-time working in secondary schools to alleviate teacher supply challenges.

Another report, published by the Department for Education (DfE) in 2018 and focusing specifically on those returning to teaching after time away, also points towards the need for more flexibility.

“Most of the 30 supported returners we interviewed said they were looking for support at a school near to where they lived that they could access at a convenient time.

“Several [teachers] said it had been important to plan a timetable of support around their other commitments, such as childcare and work,” the report states.

Ultimately, it’s obvious that the more flexible a job is, the more attractive it is to stay in, says Gascoigne.

“The case for flexibility across the whole of the modern workforce is so well documented in terms of attraction and retention. I think it would be very odd if it wasn’t true of teaching as well as the rest of the workforce. It’s an expectation now in a way that it wasn’t even 20 years ago, let alone 30 or 40 years ago,” she explains.

So, with the case clear for introducing more flexibility in teaching, how should the sector actually go about it? Is it a case of scrapping everything we think we know about working patterns and starting from scratch?

Leaders, you can breathe a sigh of relief: there is already some innovative work going on in this area to learn from that does not require a complete rethink of the school day.

In April this year, the DfE attempted to give that innovative work a wider airing, revealing that eight schools that are already leading in this area would take part in a pilot to encourage others to explore similar approaches. Just the fact that these schools will give other leaders some different ideas to play with is a huge step, says Turner, as the profession, she believes, has a very limited view about flexible working.

“In education, we have got a very set mindset about what flexible working looks like,” she argues. “I don’t think people realise the flexibility that can be on offer in a CEO, headship and classroom teacher role because, historically, it’s only ever been a job share in a class teacher role. Actually, it’s so much broader than that and there are many different ways of doing it: flexibility within full-time roles, within part-time roles and over the course of your career as well.”

According to the CIPD, there are 11 different types of flexible working (see box, page 25) and, indeed, in the Department for Education’s own guidance on flexible working patterns in education, nine different approaches are mentioned (see box, right).

The truth is, though, there may be many more just waiting to be discovered and some may be context dependent to your circumstances. So, if the first step to a more flexible future is making people aware that thinking outside the box should be encouraged, the second step is to find a way of helping them to do that.

In the Timewise report, Gascoigne suggests a six-step approach to introducing flexibility: build a team to lead and drive change; determine feasible goals; communicate, consult and challenge perceptions; explore options for job design and timetabling; pilot your chosen approach; and integrate flexible principles across the school.

At the centre of all these steps should be a focus on a “whole-school approach”, she argues. “It’s really difficult to do it on an individual basis,” she says.

“If you wait for teachers to request [flexible working], you end up with an accumulation of accommodation. It might be that a leader thinks: ‘I can accommodate the first person who asks and then I’ll make a special arrangement for the second person who asks but, by the time it gets to the third person, I really can’t make this work anymore’.”

So, what do the six steps look like in practice? According to the report, you should start with forming a small working group, with representatives from a range of roles in the school, including leaders, as well as perhaps governors or parents.

The group should build the school’s business case for flexible working, looking at additional costs versus projected savings and the impact on staff numbers. It should also reflect on the successes and failures of any existing flexible-working policy.

This feeds into the next step of determining feasible goals, which is all about being self-critical: do you tolerate flexible working, but reluctantly? Do you welcome it reactively or do you proactively support it?

The working group should agree on a set of aims, thinking about how to tackle flexible working for existing staff, flexible hiring and opportunities for progression on a part-time or flexible basis.

The third step - communicate, consult and challenge perceptions - is about identifying the key stakeholders, such as staff, governors and parents, whose support and understanding is essential, and mapping out what their communication needs are.

This includes considering any cultural barriers to flexible working that might exist within the school community and how to overcome them.

You should also try to get a sense of the unmet demand for flexible working among staff through surveys or focus groups.

Creative solutions

Once you better understand the context you are working with, you can begin to explore options for job design and timetabling, which Gascoigne says should start with considering where, when and how much people work - and how any changes to this will affect the responsibilities, activities, outcomes and skills of the whole team, not just the jobholder.

She provides the example of late starts. As a pilot, try moving form time to just after lunch. Consider how many late starts this means you’d be able to offer and what effect it would have on registration administration and pastoral time, as well as learning time in lesson one. Make sure you measure whether students are adversely affected by the change and whether the change has a positive impact on staff.

Finally, you need to future proof your approach by integrating flexible principles across the school.

This includes ensuring that jobs are advertised as flexible, having proactive conversations at interview and offering face-to-face meetings with existing staff to talk through their needs.

Schools should also consider the scope for flexible working at senior level and encourage talented staff who work flexibly to apply for more senior roles.

“The schools that are successful - and there are ones which have a half or a third of teaching staff working flexibly - are the ones in which the leaders are much more proactive about timetables and less scared about the logistics of flexible working,” says Gascoigne.

“It should be seen as an extra management task. Leaders need to be asking every single teacher, every year: what do you want, what would make a difference to your work-life balance?”

The nature of the work that goes on in schools means that leaders will need to find creative solutions here. But the wheel does not need reinventing.

Looking outside of education can bring useful ideas. In the construction world, for example, there are some great practices that can translate: practices that centre on the parts of the job that can be done remotely.

“Construction has some of the same constraints as teaching in terms of where people work because, obviously, you can’t build a building remotely.

“On the other hand, there are bits of the job that you can sort of bundle together and do remotely, and that same principle applies in teaching, where staff could do planning, preparation and assessment time, or log in to remote meetings, from home.

“It’s really about understanding the work as well as people’s fears and concerns,” Gascoigne says.

But while we should encourage leaders to look beyond the school gates for good practice, they should also look within the sector, says Turner, as “there are great pockets of practice in schools around flexible working”.

So, how are some schools already doing things differently and what can other schools learn from them?

Oppositional issues

Emma Stewart is the development director at Timewise. Through a pioneer programme run by her organisation, she has worked with three multi-academy trusts that are actively introducing flexibility.

She says that where schools are doing this well, they have focused on three things: timetabling, guidance and being “reason neutral”.

With timetabling, she points towards Huntington School in York. Every September, leaders ask staff to make their flexible requests for the following year by November. The requirements are then confirmed by February, after Years 10 and 12 have chosen their options.

As the timetable is built, the requests are made into a reality. This can mean splitting classes or arranging job shares - which, critically, leaders are OK with.

“Split classes are quite contentious. There is often a real anxiety that if you make too many split classes, if you make too many adjustments in the context of teachers particularly working part-time, that will have a negative impact on student attainment,” says Stewart. However, if flexible working is approached in the right way, concerns about split classes and job shares cease to be “oppositional issues”.

Disseminating guidance to every teacher is crucial, she says. That guidance needs to “demonstrate that the school is open to conversations about flexibility” and offer examples of what that might look like, including “job shares, reducing hours from five days a week to three”.

It should also set out the school’s position on “hours physically spent in school versus time spent at home” and on “required attendance for non-teaching activities”.

But flexible working should not be presented as a “one-size-fits-all solution”, she continues. “It’s not about laying down rules and saying ‘this is our policy’ - it’s about having guidance which empowers teachers to have open conversations.”

Where flexibility has worked well, leaders don’t consider one person’s reasons for requesting flexible working to be more valid than the next person’s, she points out.

“Reasons are becoming more and more varied: caring has been the obvious one,” she says, “[But] we’ve had more unusual things. We’ve had people who negotiated to work flexibly because they’re writing an opera; others have wanted time for academic studies. There’s all kinds of reasons and there shouldn’t be a hierarchy of need.”

So, should leaders feel pressure to accept any request for flexible working?

Mandy Coalter, an HR professional and the founder of Talent Architects, an education HR consultancy firm, stresses that being open to requests doesn’t mean you have to just say “yes” to everything.

“It’s not about saying, ‘tell us what you want and you can have it’,” she says. “It’s about saying, ‘tell us what your life is like and what you need from us’.”

Leaders don’t always need to agree outright to a flexible-working request, then, particularly if it is not the best choice for the school in the circumstances.

But nor should they be automatically refusing requests without due consideration either. Coalter warns that doing so could place a school at a serious disadvantage in terms of its ability to recruit and retain the best staff.

Ultimately, if your default position on flexible working is “why?”, remember that there could be a senior leadership team at the school down the road asking, “why not?”. Which do you think is more attractive to great teachers?

Kate Parker is schools and colleges content producer at Tes

This article originally appeared in the 1 October 2021 issue under the headline “The future is flexible”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article